6 Accelerating Applications

6.1 Property Prediction

general-purpose model (GPM)s have emerged as a tool for predicting molecular and material properties. Current examples of GPM-driven property prediction span both classification and regression from standardized benchmarks such as MoleculeNet [Wu et al. (2018)], to curated datasets targeting specific applications such as antibacterial activity [Chithrananda, Grand, and Ramsundar (2020)] or photovoltaic efficiency [Aneesh et al. (2025)].

Three key methodologies have been explored to adapt these models for property prediction: prompting techniques (see Section 3.11.1), fine-tuning (see Section 6.2.1.2) on domain-specific data, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) (see Section 3.12.1.3) approaches that combine models with external knowledge bases.

| Model | Property | Dataset | Approach | Task |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM-Prop (Rubungo et al. 2023) | Band Gapj | CrystalFeatures-MP2022 (Rubungo et al. 2023) | P | R |

| Volume | CrystalFeatures-MP2022 (Rubungo et al. 2023) | P | R | |

| Band Gap | CrystalFeatures-MP2022 (Rubungo et al. 2023) | P | C | |

| LLM4SD (Zheng et al. 2025) | Blood-brain Barrier Penetration | BBBP (Sakiyama, Fukuda, and Okuno 2021) | P | C |

| FDA Approval | ClinTox (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| Toxicology | Tox21 (Richard et al. 2021) | P | C | |

| Drug-related Side Effects | SIDER (Kuhn et al. 2016) | P | C | |

| HIV Replication Inhibition | HIV (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| β-secretase Binding | BACE (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| Solubility | ESOL (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| Hydration Free Energy | FreeSolv (Mobley and Guthrie 2014) | P | R | |

| Lipophilicity | Lipophilicity (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| Quantum Mechanics | QM9 (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| Domain Knowledge Prompt-Engineering (H. Liu et al. 2025) | Crystal | Custom (H. Liu et al. 2025) | P | C, R |

| Organic Small Molecules | PubChem | P | C, R | |

| Enzymes | UniProt | P | C, R | |

| Molecular GPT (Y. Liu et al. 2024) | β-secretase Binding | BACE (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C |

| HIV Replication Inhibition | HIV (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| Bioactivity | MUV (Rohrer and Baumann 2009) | P | C | |

| Toxicology | Tox21 (Richard et al. 2021) | P | C | |

| Toxicology | ToxCast (US EPA n.d.) | P | C | |

| Blood-brain Barrier Penetration | BBBP (Sakiyama, Fukuda, and Okuno 2021) | P | C | |

| Cytochrome P450 isozymes | CYP450 (Ni et al. 2025) | P | C | |

| Solubility | ESOL (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| Hydration Free Energy | FreeSolv (Mobley and Guthrie 2014) | P | R | |

| Lipophilicity | Lipophilicity (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| GPT-MolBERTa (Balaji et al. 2023) | Blood-brain Barrier Penetration | BBBP (Sakiyama, Fukuda, and Okuno 2021) | P | C |

| Toxicology | Tox21 (Richard et al. 2021) | P | C | |

| Toxicology | ToxCast (US EPA n.d.) | P | C | |

| FDA Approval | ClinTox (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| Solubility | ESOL (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| Hydration Free Energy | FreeSolv (Mobley and Guthrie 2014) | P | R | |

| Lipophilicity | Lipophilicity (Wu et al. 2018) | P | R | |

| HIV Replication Inhibition | HIV (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| β-secretase Binding | BACE (Wu et al. 2018) | P | C | |

| GPT-Chem (Jablonka et al. 2024) | HOMO/LUMO | QMUGs (Isert et al. 2022) | FT | C, R |

| Solubility | DLS-100 (Mitchell 2017) | FT | C, R | |

| Lipophilicity | LipoData (Jablonka et al. 2024) | FT | C, R | |

| Hydration Free Energy | FreeSolv (Mobley and Guthrie 2014) | FT | C, R | |

| Photoconversion Efficiency | OPV (Jablonka et al. 2024) | FT | C, R | |

| Toxicology | Tox21 (Richard et al. 2021) | FT | C, R | |

| \(\text{CO}_{2}\) Henry coeff. of MOFs | MOFSorb-H (L.-C. Lin et al. 2012) | FT | C, R | |

| LLaMP (Chiang et al. 2024) | Bulk modulus | Materials Project (Riebesell et al. 2025) | RAG | R |

| Formation energy | Materials Project (Riebesell et al. 2025) | RAG | R | |

| Electronic band gap | Materials Project (Riebesell et al. 2025) | RAG | R | |

| Multi-element band gap | Materials Project (Riebesell et al. 2025) | RAG | R |

Key: P = prompting; FT = fine-tuned model; RAG = retrieval-augmented generation; C = classification; R = regression

6.1.1 Prompting

Prompt engineering involves designing targeted instructions to guide GPMs in performing specialized tasks without altering their underlying parameters. In molecular and materials science, this strategy goes beyond simply asking a model to predict properties. Prompting strategies for molecular property prediction have evolved from foundational techniques like domain-knowledge and few-shot reasoning [H. Liu et al. (2025)] to more advanced methods with multi-modal frameworks that extract interpretable rules [Zheng et al. (2025)] (see Table 6.1).

Another emerging application of large language model (LLM)-based GPMs is their use as “feature extractors”, where they generate textual or embedded representations of molecules or materials. For instance, in materials science, Aneesh et al. (2025) employed LLMs to generate text embeddings of perovskite solar cell compositions. These embeddings were subsequently used to train a graph neural network (GNN) for predicting power conversion efficiency, demonstrating the potential of LLMs to enhance feature representation in materials informatics.

chain-of-thought (CoT) Prompting[Srinivas and Runkana (2024)]

Prompt 1: What is the molecular structure of this chemical simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) string? Could you describe its atoms, bonds, functional groups, and overall arrangement?

Prompt 2: What are the physical properties of this molecule, such as its boiling point and melting point?

…

Prompt 14: Are there any environmental impacts associated with the production, use, or disposal of this molecule?

Similarly, in the molecular domain, Srinivas and Runkana (2024) used zero-shot LLM prompting (see Note 6.1 for prompt examples) to generate detailed textual descriptions of molecular functional groups, which are used to train a small language model (LM). This LM is used to compute text-level embeddings of molecules. Simultaneously, they generate molecular graph-level embeddings from SMILES string molecular graph inputs. They finally integrate the graph and text-level embeddings to produce a semantically enriched embedding.

6.1.2 Fine-Tuning

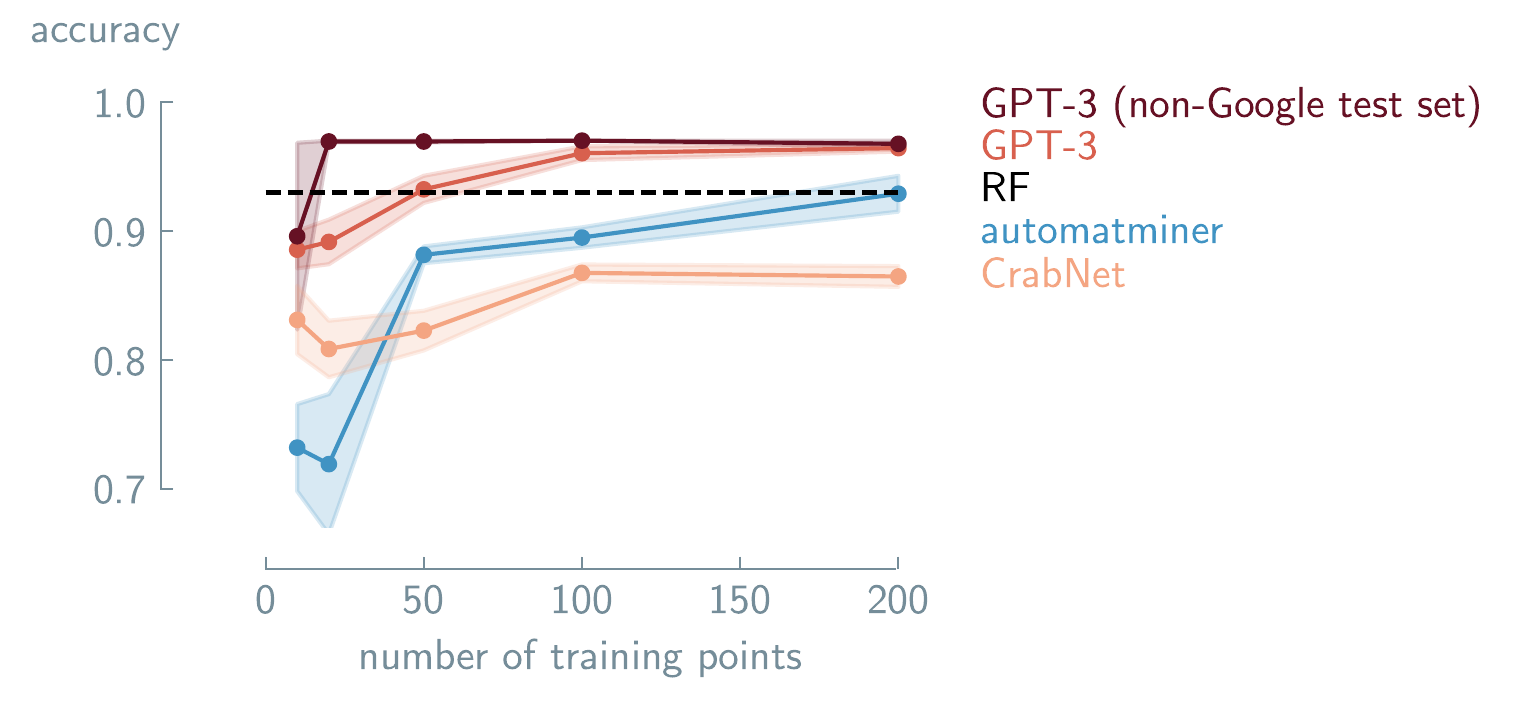

GPT-3 for predicting solid-solution formation in high-entropy alloys. Performance comparison of different machine learning (ML) approaches as a function of the number of training points. Results are shown for Automatminer (blue), CrabNet transformer (orange), fine-tuned GPT-3 (red), with error bars showing standard error of the mean. The non-Google test set shows the fine-tuned GPT-3 model tested on compounds without an exact Google search match (dark red). The dashed line shows performance using random forest (RF). GPT-3 achieves comparable accuracy to traditional approaches with fewer training examples. Data adapted from Jablonka Jablonka et al. (2024). Copyright 2024 Jablonka et al./Springer Nature.

6.1.2.1 language-interfaced finetuning (LIFT)

Dinh et al. (2022) showed that reformulating regression and classification as questions & answers (Q&A) tasks enables the use of an unmodified model architecture while improving performance (see Section 6.2.1.2 for a deeper discussion of LIFT). In recognizing the scarcity of experimental data and acknowledging the persistence of this limitation, Jablonka et al. (2024) designed a LIFT-based framework using GPT-3 fine-tuned on task-specific small datasets (see Table 6.1). They demonstrated that fine-tuned GPT-3 can match or surpass specialized ML models in various chemistry tasks (as shown in Figure 6.1).

In a follow-up to Jablonka et al. (2024)’s work, Van Herck et al. (2025) systematically evaluated this approach across 22 diverse real-world chemistry case studies using three open-source models. They demonstrate that fine-tuned LLMs can predict various material properties. For example, they achieved \(96\%\) accuracy in predicting the adhesive free-energy of polymers, outperforming traditional ML methods like random forest (\(90\%\) accuracy). The LLMs can also work with non-standard inputs, like for predicting protein phase separation, where raw protein sequences could be directly input without pre-processing and achieve \(95\%\) prediction accuracy. At the same time, when training datasets were very small (15 data points), the predictive accuracy of all fine-tuned models was lower than the random baseline (e.g., MOF synthesis). These case studies preliminarily demonstrate that these models can achieve predictive performance with some small datasets, work with various chemical representations (SMILES, metal-organic framework (MOF)id, and International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) names), and can outperform traditional ML approaches for some material property prediction tasks.

In the materials domain, LLMprop fine-tunes T5[Raffel et al. (2020)] to predict crystalline material properties from text descriptions generated by Robocrystallographer[Ganose and Jain (2019)]. By discarding T5’s decoder and adding task-specific prediction heads, the approach reduces computational overhead while leveraging the model’s ability to process structured crystal descriptions.

Fine-tuning has also been applied to non-LLM architectures, specifically to selective state space model (SSM)s like Mamba (see Section 3.8). By pre-training on 91 million molecules, the Mamba-based model \(\text{O}_{SMI}-{\text{SSM}-}336\textit{M}\) outperformed transformer methods (Yield-BERT[Krzyzanowski, Pickett, and Pogány (2025)]) in reaction yield prediction (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling) and achieved competitive results in molecular property prediction benchmarks.[Soares et al. (2025)]

6.1.3 Agents

Caldas Ramos et al. introduced MAPI-LLM, a framework that processes natural-language queries about material properties using an LLM to decide which of the available tools, such as the Materials Project application programming interface (API), the Reaction-Network package, or Google Search, to use to generate a response. [Jablonka et al. (2023)] MAPI-LLM employs a reasoning and acting (ReAct) prompt (see Section 3.12.1 to read more about ReAct), to convert prompts such as “Is \(Fe_2O_3\) magnetic?” or “What is the band gap of Mg(Fe3O3)2?” into queries for Materials Project API. The system processes multi-step prompts through logical reasoning, for example, when asked “If Mn2FeO3 is not metallic, what is its band gap?”, the LLM system creates a two-step workflow to first verify metallicity before retrieving the band gap.

Building on this foundation of agent-based materials querying, Chiang et al. (2024) advanced the approach with LLaMP, a framework that employs “hierarchical” ReAct agents to interact with computational and experimental data. This “hierarchical” framework employs a supervisor-assistant agent architecture where a complex problem is broken down and tasks are delegated to domain-specific agents.

6.1.4 Limitations

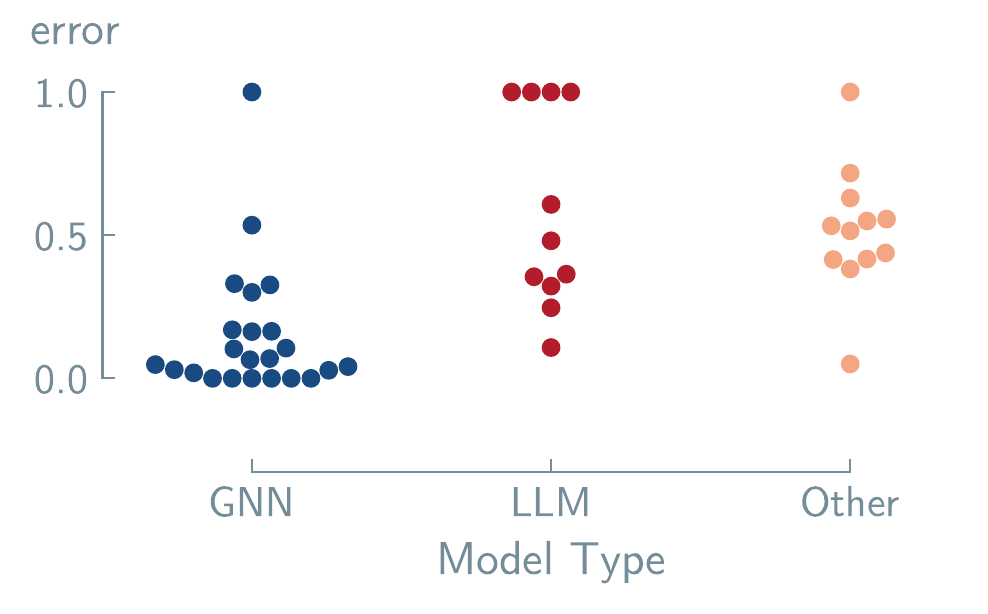

CrabNet. (A. Y.-T. Wang et al. 2021) Lower values indicate better predictive performance. Data adapted from Alampara, Miret, and Jablonka (2024).

A significant challenge for GPMs in chemistry lies in managing dataset limitations and selecting appropriate chemical representations. Practical applications often suffer from highly unbalanced datasets, where examples of optimal materials are vastly outnumbered by poor-performing ones, forcing difficult compromises that can diminish model performance [Van Herck et al. (2025)]. The choice of how a material is represented (SMILES notation versus IUPAC) also critically impacts performance, indicating that data preprocessing remains a crucial consideration.

Beyond data issues, architectural constraints present another barrier as illustrated in Figure 6.2. Alampara, Miret, and Jablonka (2024) reveal that while LLMs are effective for tasks relying on compositional information, they struggle to interpret geometric or spatial data when it is encoded in text. This suggests a fundamental limitation of transformer-based architectures for applications requiring spatial reasoning. Consequently, the conventional assumption that performance can be universally improved by scaling up model size or pre-training data is challenged [Frey et al. (2023)]. Such scaling may not overcome the inherent bias against geometric understanding.

6.1.5 Open Challenges

Encoding 3D Structure: Developing methods to effectively represent and integrate geometric, spatial, and structural information to overcome their inherent bias toward compositional data.

Dynamic Knowledge Integration: Move beyond static fine-tuning to establish a reliable, real-time framework that can incorporate new, evolving scientific findings without catastrophic forgetting.

Fundamental Architectural Shifts: Exploring whether many of the existing GPM architectures are sufficient or if new, specialized ones are needed to capture complex relationships in molecular and materials science.

6.2 Molecular and Material Generation

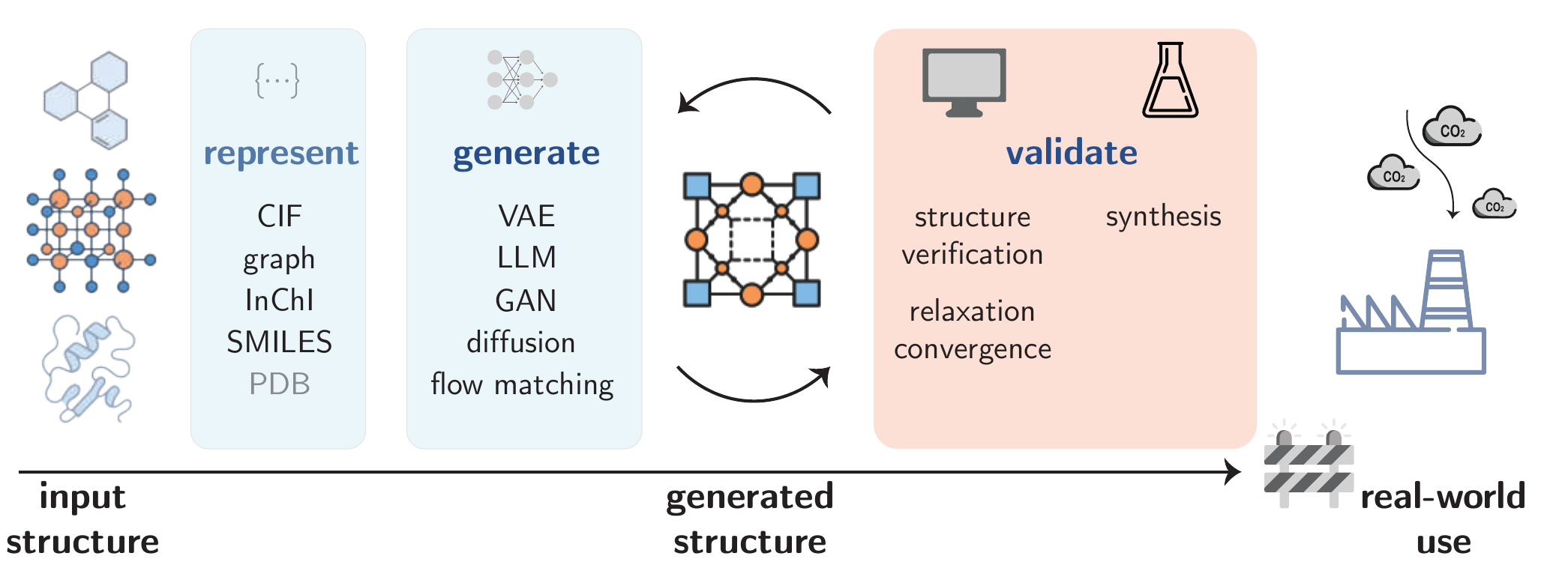

Early work in molecular and materials generation relied heavily on unconditional generation, where models produce novel structures without explicit guidance. These methods excel at exploring chemical space broadly but lack specific control. Conditional generation, in contrast, uses explicit prompts or constraints (e.g., property targets, structural fragments) to steer GPMs toward meaningful molecule or material designs. Beyond the generation step, as Figure 6.3 shows, critical bottlenecks persist in synthesizability and physical consistency at the validation stage.

6.2.1 Generation

6.2.1.1 Prompting

While zero-shot and few-shot prompting strategies offer a flexible approach to molecule generation, benchmark studies [Guo et al. (2023)] reveal a significant performance gap compared to specialized models. Guo et al. (2023) systematically evaluated LLMs like GPT-4, finding that while they could generate syntactically valid molecules (\(89\%\) validity), their accuracy in meeting specific property targets was low (\(< 20\%\)). These performance gaps highlight the lack of chemical structure-property relationships possessed by LLMs.

6.2.1.2 Fine-Tuning

To overcome the limitations of prompting, fine-tuning has been adopted in molecular and materials generation, much like its use in property prediction with LIFT-based frameworks (see Section 6.2.1.2 for a deeper explanation of LIFT and Section 6.1.2 for a discussion of LIFT applied to property prediction tasks).

A representative example is in-context molecule adaptation (ICMA), which combines retrieval-augmented in-context learning with fine-tuning [J. Li et al. (2025)]. This method avoids extensive domain-specific pre-training by retrieving relevant examples to guide the model. On standard benchmarks, ICMA nearly doubled baseline performance for tasks like generating molecules from text descriptions (Cap2Mol). However, its strong dependence on retrieved examples raises questions about its ability to generalize to entirely novel molecular scaffolds. Other fine-tuning approaches have aimed to further improve accuracy on the “Cap2Mol” task [J. Li et al. (2024); X. Lin et al. (2025)].

6.2.1.3 Diffusion and Flow Matching

Diffusion and flow-based generative models provide a flexible framework for generating diverse structures by operating directly on latent representations [Zhu, Xiao, and Honavar (2024)]. A more complex challenge involves generating crystalline materials, which require modeling both discrete (atom type) and continuous (atomic position) variables. To address this, hybrid architectures like FLowLLM have emerged, combining the strengths of LLMs and flow matching. In this approach, a fine-tuned LLM learns a base distribution of crystals from text-based representations, which is then refined through rectified flow matching to optimize the atomic structure [Sriram et al. (2024)].

6.2.1.4 Reinforcement Learning and Preference Optimization

Translating GPM generated outputs to the real world requires designing molecules and materials with specific target properties. reinforcement learning (RL) and preference optimization techniques[D. Lee and Cho (2024)] have emerged as potential solutions for this challenge.

CrystalFormer-RL uses RL fine-tuning to optimize CrystalFormer[Cao et al. (2024)], a transformer-based crystal generator, with rewards from discriminative models (e.g., property predictors)[Cao and Wang (2025)]. Here, RL fine-tuning is shown to outperform supervised fine-tuning, enhancing both novel material discovery and retrieval of high-performing candidates from the pre-training dataset.

energy ranking alignment (ERA) introduces a different optimization paradigm. [Chennakesavalu et al. (2025)] Unlike proximal policy optimization (PPO) or direct preference optimization (DPO), ERA uses gradient-based objectives to guide word-by-word generation with explicit reward functions, converging to a physics-inspired probability distribution that allows fine control over the generation process.

6.2.1.5 Agents

Agent-based frameworks leveraging LLMs, explained in Section 3.12, have emerged as approaches for autonomous molecular and materials generation, demonstrating capabilities that extend beyond simple prompting or fine-tuning by incorporating iterative feedback loops, tool integration, and human-artificial intelligence (AI) collaboration. The dZiner framework exemplifies this approach for the inverse design of materials, where agents input initial SMILES strings with optimization task descriptions and generate validated candidate molecules by retrieving domain knowledge from the literature.[Ansari et al. (2024)] It also uses domain-expert surrogate models to evaluate the required property in the new molecule/material.

6.2.2 Validation

6.2.2.1 General validation

The most fundamental validation approaches use cheminformatics tools like RDKit to verify molecular validity. More sophisticated validation involves quantum mechanical calculations to compute molecular properties such as formation energies[Kingsbury et al. (2022)].

The gold standard for validation is experimental synthesis, but significant gaps exist between computational generation and laboratory realization. Retrosynthesis prediction algorithms attempt to bridge this gap by evaluating synthetic accessibility and proposing potential synthesis routes (see Section 6.3). However, these methods still face limitations in accurately predicting real-world synthesizability [Zunger (2019)].

6.2.2.2 Conditional Generation Validation

Beyond establishing the general validity of generated molecules, evaluation methods can assess both their novelty relative to training data and their ability to meet specific design goals. For inverse design tasks, such as optimizing binding affinity or solubility, the de novo molecule generation benchmark GuacaMol differentiates between distribution-learning (e.g., generating diverse, valid molecules) and goal-directed optimization (e.g., rediscovering known drugs or meeting multi-objective constraints) [Brown et al. (2019)]. In the materials paradigm, frameworks such as MatBench Discovery evaluate analogous challenges such as stability, electronic properties, and synthesizability, but adapt metrics to periodic systems, such as energy above hull or band gap prediction accuracy[Riebesell et al. (2025)].

6.2.3 Limitations

Current generative pipelines for molecules and materials, as illustrated in Figure 6.3, face significant bottlenecks that limit their immediate real-world application. A primary limitation is the performance gap in conditional generation; while methods like fine-tuning and reinforcement learning have improved control, LLMs often lack the inherent chemical understanding to accurately meet specific property targets. Furthermore, the validation stage remains a critical challenge. Even when a structure is computationally valid, assessing its synthesizability and physical consistency relies heavily on approximations, with a significant gap remaining between in-silico prediction and experimental realization.

6.2.4 Open Challenges

Robust Conditional Generation Developing models that can reliably generate novel, diverse structures that satisfy complex, multi-objective constraints (e.g., high stability, specific electronic properties, and synthesizability) without over-relying on retrieved training data examples.

Bridging the Synthesis Gap Creating new validation metrics that better predict the synthetic feasibility of generated materials and molecules, moving beyond structural similarity toward realistic pathway prediction.

Unified Multi-Scale Generation Developing frameworks that are capable of simultaneously modeling different representations (e.g., text, graphs, 3D structures) and scales (e.g., from molecules to crystalline materials) within a single generative process

6.3 Retrosynthesis

The practical utility of GPMs for molecules and materials design is constrained by uncertainty in synthetic feasibility. Early work showed that attention-based models learn meaningful reaction representations, enabling accurate reaction outcome classification and prediction [Schwaller et al. (2021)].

Building on this, generation pipelines increasingly integrate synthesizability and retrosynthetic guidance via domain tools and GPMs [G. Liu et al. (2024)]. For example, Sun et al. (2025) adapted open LLMs to propose retrosynthetic routes and identify purchasable building blocks for experimentally validated SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors.

LLMs are also being fine-tuned as chemistry assistants for experimental guidance. Zhang et al. (2025) used a two-stage process, supervised fine-tuning with reaction and retrosynthesis Q&A followed by reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) to optimize reaction conditions, achieving an unreported Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling in 15 runs.

Predictive retrosynthesis has also extended to the inorganic domain. Kim, Jung, and Schrier (2024) demonstrated that fine-tuned GPT-3.5, and GPT-4 can predict both the synthesizability of inorganic compounds from their chemical formulas and select appropriate precursors for synthesis, achieving performance comparable to specialized ML models with minimal development time and cost.

Toward autonomy, Bran et al. (2024) developed ChemCrow, an LLM-based system that autonomously plans and executes the synthesis of novel compounds by integrating specialized tools like a retrosynthesis planner (see Section 5.5 to read more about this capability of ChemCrow and its limitations) and reaction predictors. This approach mirrors the iterative experimental design cycle employed by human chemists, but is equipped with the scalability of automation.

6.3.1 Limitations

GPMs inherit the fundamental constraints associated with domain-specific models for retrosynthesis, which primarily concern data and evaluation methodologies. The prevailing reliance on patent-derived data introduces a significant bias, as these datasets are dominated by a limited set of reaction types and predominantly feature single-step examples. Furthermore, the absence of negative results and the frequent omission of experimental conditions can mislead model training [C. Lee et al. (2024); Voinarovska et al. (2023); Saebi et al. (2023); Maloney et al. (2023); Tadanki, Surya Prakash Rao, and Priyakumar (2025)]. The evaluation paradigms suffer from a parallel shortcoming, as they are largely designed for single-step routes and fail to adequately capture the complexities of real-world, multi-step case studies [Torren-Peraire et al. (2024); Maziarz et al. (2025); S. Liu et al. (2024)].

A further significant challenge is data leakage. The vast scale of data used for training these models often leads to saturated benchmarks, where high performance may reflect memorization rather than genuine generalization.

Finally, while standalone GPMs shows limited efficacy for multi-step retrosynthesis, its integration into agentic frameworks introduces a distinct set of limitations. Current evaluations are poorly suited to assess the critical components of such systems, such as planning, reasoning, and tool-calling capabilities. The focus remains predominantly on final answer correctness, which impedes large-scale optimization and correction of agents without extensive human oversight, typically resulting in the use of a fragile and error-prone LLM-as-Judge.

These evaluation gaps, combined with the inherent limitations in long-term planning and chemical understanding of the underlying LLMs, present substantial obstacles to the development and practical application of agentic systems for this retrosynthetic task.

6.3.2 Open Challenges

Data Quality and Bias: To build more robust and generalizable models, the field must integrate higher-quality data from peer-reviewed scientific literature. This requires the development of standardized extraction schemas and data cleaning protocols to create a balanced and reliable training corpus [Rı́os-Garcı́a and Jablonka (2025); Mehr et al. (2020)].

Robust and Meaningful Evaluation: There is a critical need for evaluation methodologies that prevent data leakage and test genuine model understanding. Benchmarks must be designed to go beyond memorization, instead probing a model’s capacity for chemical reasoning, generalization to novel structures, and robust problem-solving.

Benchmarking Complex Planning: Truly assessing a GPM’s utility requires benchmarks that mirror real-world complexity. This involves evaluating performance in open-ended retrosynthetic planning and developing frameworks that assess a model’s sequential decision-making.

6.4 GPMs as Optimizers

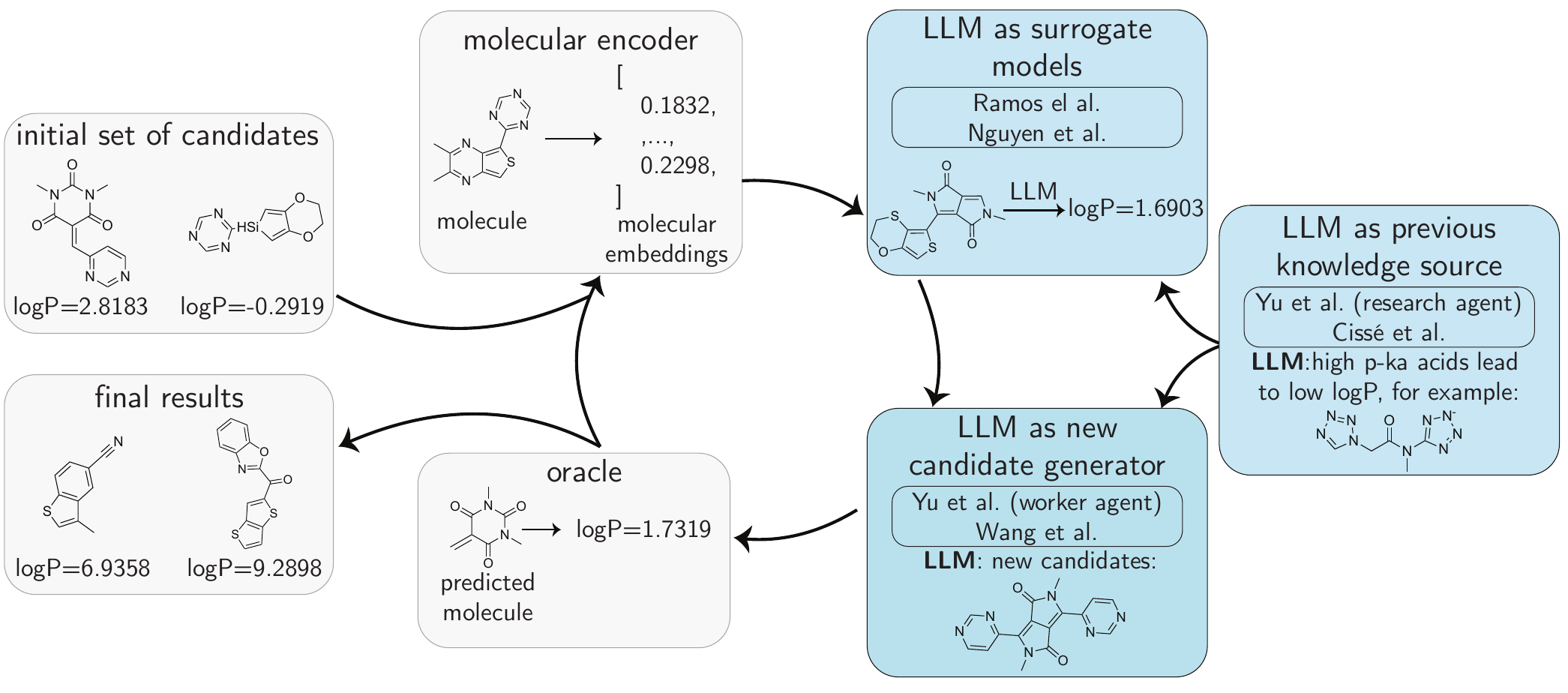

logP.

Discovering novel compounds and reactions in chemistry and materials science has long relied on iterative trial-and-error processes rooted in existing domain knowledge [Taylor et al. (2023)]. As noted in Section 6.3, these methods accelerate discovery, and optimization targets variables such as conditions or binding affinity. Nevertheless, the overall process remains slow and labor-intensive. Traditional data-driven methods aim to address these limitations by combining predictive ML models with optimization frameworks such as Bayesian optimization (BO) or evolutionary algorithm (EA)s. These frameworks balance exploration of uncharted regions in chemical space with exploitation of known high-performing regions [X. Li et al. (2024); Häse et al. (2021); Shields et al. (2021); Griffiths and Hernández-Lobato (2020); Rajabi-Kochi et al. (2025)].

Recent advances in LLMs have been explored for targeting optimization challenges in chemistry and related domains [Fernando et al. (2023); Yang et al. (2023); Chen et al. (2024)]. A commonly referenced advantage is that LLMs may process optimization tasks posed in natural language, which may facilitate knowledge incorporation, candidate comparison, and interpretability in some settings. This can align with chemical problem-solving, where complex phenomena, such as reaction pathways or material behaviors, are often poorly captured by standard nomenclature; however, they can still be intuitively explained through natural language. Moreover, GPMs can offer flexibility when problem definitions change, whereas many classical models require retraining. Encoding domain-specific knowledge—including reaction rules, thermodynamic principles, and structure-property relationships—into structured prompts may allow LLMs to complement domain expertise with their ability to navigate complex chemical optimization problems.

Current LLM applications in chemistry optimization vary in scope and methodology. Many studies integrate LLMs into BO frameworks, where models guide experimental design by predicting promising candidates [Ranković and Schwaller (2023)]. Others employ genetic algorithm (GA)s or hybrid strategies that combine LLM-generated hypotheses with computational screening [Cissé et al. (2025)].

6.4.1 LLMs as Surrogate Models

A prominent LLM-driven strategy positions these models as surrogate models within optimization loops [Yu et al. (2025)]. Surrogate models—often implemented as Gaussian process regression (GPR)—learn from prior data to approximate costly feature-outcome landscapes, which are often computationally expensive and time-consuming to evaluate, thereby guiding the acquisition. A proposed advantage of the LLMs in this role is relatively better low-data performance compared to classical ML optimization methods. Their in-context learning (ICL) capability enables task demonstration with minimal prompt examples while leveraging chemical knowledge from pre-training to generate accurate predictions. This allows LLMs to compensate for sparse experimental data effectively. However, LLMs are less robust than GPR due to their tendency to hallucinate.

Ramos et al. (2023) demonstrated the use of this low-data regime through a framework that combines ICL using only one example in the prompt with a BO workflow. Their BO-ICL approach uses \(k\)-shot examples formatted as question-answer pairs, where the LLM generates candidate solutions conditioned on prior successful iterations. These candidates are ranked using an acquisition function, with top-\(k\) selections integrated into subsequent prompts to refine predictions iteratively. Interestingly, in the reported experiments, the method performed competitively, matching top-1 accuracies on the evaluated benchmarks compared to classical BO methods. This emphasizes the potential of LLMs as accessible, ICL optimizers when coupled with well-designed prompts.

Trying to address limitations in base LLMs’ inherent chemical knowledge—particularly their grasp of specialized representations like SMILES or structure-property mappings—Yu et al. (2025) introduced a hybrid architecture augmenting pre-trained LLMs with task-specific embedding and prediction layers. These layers, fine-tuned on domain data, aligned latent representations of input-output pairs (denoted as <x> and <y> in prompts), enabling the model to map chemical structures and properties into a unified, interpretable space. Crucially, the added layers were reported to improve chemical reasoning without sacrificing the flexibility of ICL, allowing the system to adapt to trends across iterations, similarly to what was done by Ramos et al. (2023). In their evaluations of molecular optimization benchmarks, such as the practical molecular optimization (PMO) [Gao et al. (2022)], they revealed that LLM-based methods matched or improved over conventional methods, including BO-Gaussian process (GP), RL methods, and GA.

6.4.2 LLMs as Next Candidate Generators

Recent studies explore the possibility of using LLMs in enhancing EAs [Lu et al. (2025)] and BO [Amin, Raja, and Krishnapriyan (2025)] frameworks by leveraging their embedded chemical knowledge and ability to integrate prior information, thereby potentially reducing computational effort while improving output quality [Lu et al. (2025)]. Within EAs, LLMs refine molecular candidates through mutations (modifying molecular substructures) or crossovers (combining parent molecules). In BO frameworks, they serve as acquisition policies, utilizing surrogate model predictions—both mean and uncertainty—to select optimal molecules or reaction conditions for evaluation.

For molecule optimization, Yu et al. (2025) introduced MultiMol, a dual-LLM system where one model proposes candidates and the other supplies domain knowledge (see Section 6.4.3). By fine-tuning the “worker” LLM to recognize molecular scaffolds and target properties, and expanding the training pool to include a pre-training dataset of \(\sim1\) million samples, they report hit rates (percentage of generated molecules that meet the target properties under a certain threshold) exceeding \(90\%\) on their evaluation set.

Similarly, H. Wang, Skreta, et al. (2025) developed MoLLEO, integrating an LLM into an EA to replace random mutations with LLM-guided modifications. Here, GPT-4 generated optimized offspring from parent molecules that converged faster to high fitness scores in the reported experiments. Notably, while domain-specialized models (BioT5, MoleculeSTM) underperformed, the general-purpose GPT-4 excelled—suggesting the utility of LLMs may be context-dependent.

6.4.3 LLMs as Prior Knowledge Sources

A key advantage of integrating LLMs into optimization frameworks is their ability to encode and deploy prior knowledge within the optimization loop. As illustrated in Figure 6.4, this knowledge can be directed into either the surrogate model or candidate generation module, potentially reducing the number of optimization steps required through high-quality guidance if the feedback is useful.

For example, Cissé et al. (2025) introduced BORA, which contextualizes conventional black-box BO using an LLM. BORA maintains standard BO as the core driver, but strategically activates the LLM when progress stalls. This leverages the model’s ICL capabilities to hypothesize promising search regions and propose new samples, regulated by a lightweight heuristic policy that manages costs and incorporates domain knowledge (or user input). Evaluations on synthetic benchmarks, such as optimizing the catalyst mixture for hydrogen generation, show that BORA was reported to accelerate exploration, and outperforms the LLM-BO hybrid methods evaluated.

To potentially enhance the task-specific knowledge of the LLM generating feedback, Zhang et al. (2025) fine-tuned a Llama-2-7B model using a multitask Q&A dataset. This dataset was created with instructions from GPT-4. The resulting model served as a human assistant or operated within an active learning loop, thereby accelerating the exploration of new reaction spaces (see sec-retrosynthesis). However, as the authors note, even this task-specialized LLM produces suboptimal suggestions for optimization tasks. They remain prone to hallucinations and cannot assist with unreported reactions, but still improved upon pure classical methods in most of the evaluated applications.

6.4.4 Approaching Optimization Problems

Published works explore different ways of using LLMs for optimization problems in chemistry, from simple approaches, such as just prompting the model with some initial random set of experimental candidates and iterating [Ramos et al. (2023)], to fine-tuning models in BO fashion [Ranković and Schwaller (2025)]. A pragmatic initial step is to try a purely ICL approach, which allows one to obtain a first signal rapidly. Such results help determine whether a more complex, computationally intensive approach is necessary or whether prompt engineering is reliable for the application. Fine-tuning can be used as a way to enhance the chemical knowledge of the LLMs and can lead to improvements in optimization tasks where the model requires such knowledge to choose or generate better candidates. Fine-tuning might not be a game-changer for other approaches that rely more on sampling methods [H. Wang, Guo, et al. (2025)].

While some initial works showed that LLMs trained specifically on chemistry perform better for optimization tasks [Kristiadi et al. (2024)], other works showed that a GPMs such as GPT-4 combined with an EA outperformed all other models [H. Wang, Skreta, et al. (2025); MacKnight et al. (2025)].

6.4.5 Limitations

Current LLMs for chemical optimization, to date, exhibit a pronounced volatility, rarely yielding stable performance gains. Their outcomes are highly sensitive to prompt phrasing, and a lack of calibrated uncertainty estimates prevents their use for principled acquisition strategies. [T. Liu et al. (2024)] Furthermore, these models frequently produce hallucinations and violate critical constraints, leading to invalid chemical structures or the proposal of unsafe and infeasible experimental conditions. Alleged improvements often hinge on narrow benchmarks, extensive pre- and post-processing, or access to downstream oracles, rather than on robust chemical reasoning. Within hybrid pipelines, the specific contribution of the LLM becomes difficult to isolate.

6.4.6 Open Challenges

Correct Prompt Sensitivity: A key challenge is achieving prompt invariance, where the ranking of candidates remains stable under controlled rephrasings. Promising research directions include developing rigorous invariance tests and moving beyond discrete tokens to leverage models’ more stable hidden states [Ranković and Schwaller (2025)].

More robust evaluations: Future work should develop more robust frameworks that assess oracle realism, conduct thorough leakage audits to detect data contamination, and integrate uncertainty-aware metrics to better quantify risk and reliability.

Ablations for the specific LLM role: There is a critical need for systematic ablation studies that isolate core LLM performance from enhancements like RAG, external scorers, or tool use. Such studies are essential for fairly comparing general and fine-tuned LLMs and for understanding the source of performance gains.