8 Outlook and Conclusions

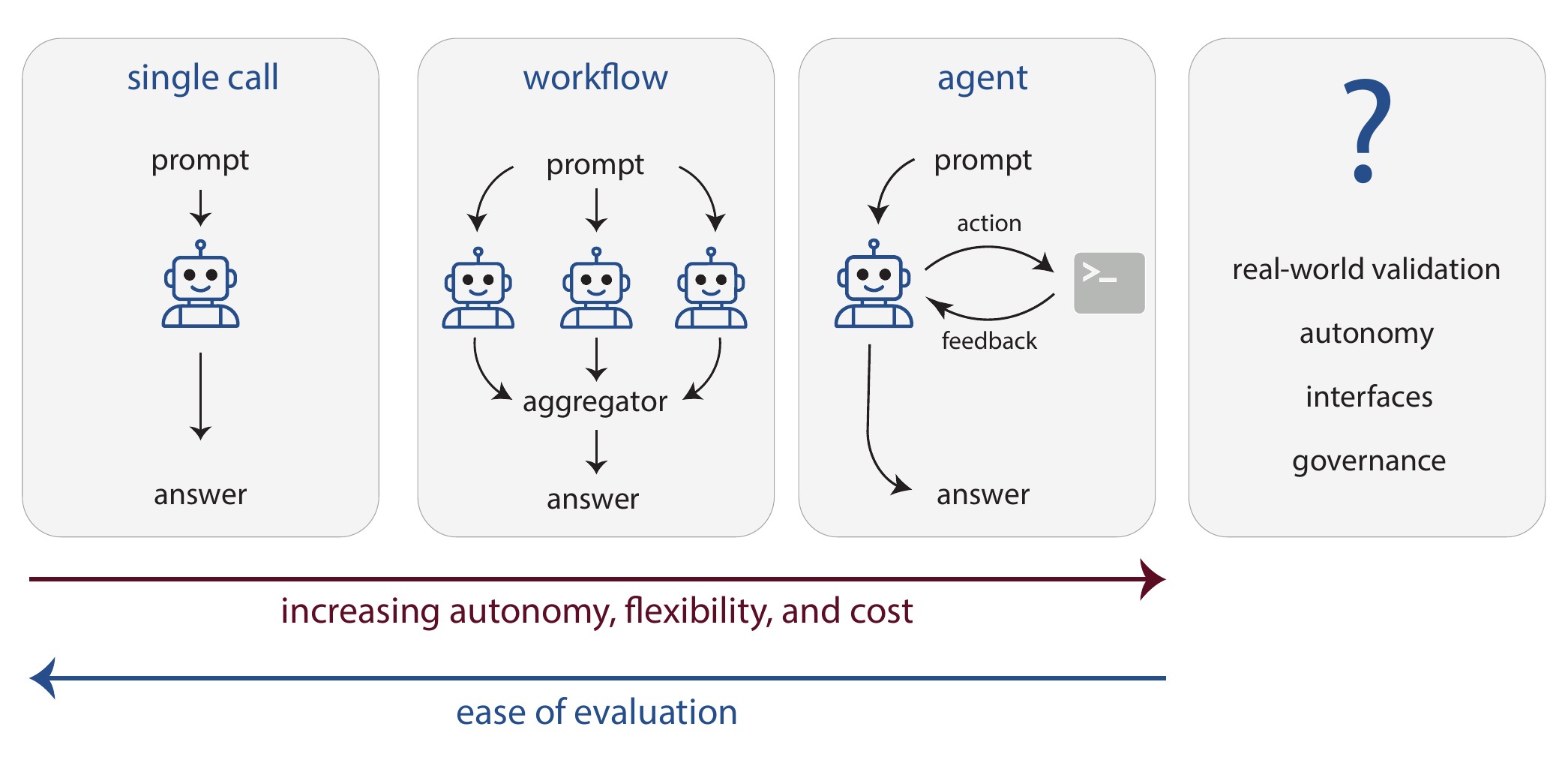

As we have explored in this review, GPMs—especially large language model (LLM)s—hold remarkable promise for the chemical sciences. The field has evolved from simple, single model calls to sophisticated workflows that chain multiple calls together, and further to the development of autonomous agents that determine their own problem-solving trajectories (see Figure 8.1).

8.1 Applicability of GPMs

With all this flexibility, it becomes tempting to deploy GPMs across a wide range of problems in the chemical sciences. However, as discussed in the previous sections, they are not always a direct replacement for existing approaches. In some cases, using a GPM may be unnecessary and inefficient. That said, there are clear scenarios where GPMs offers distinct advantages. When data is unstructured or “fuzzy”—such as text-based descriptions or incomplete experimental records lacking explicit molecular structures—GPMs, become valuable alternatives where specialized pipelines like graph neural network (GNN)s would be inapplicable. Similarly, in extremely low-data regimes where specialized pipelines or domain-specific foundation models would overfit, GPM embeddings can provide more robust predictions than random baselines. Finally, for dynamic environments that require iterative reasoning, interpretation, and adjustment of the system states, GPM-powered agents are well-suited. In contrast, when clean datasets are available and inductive biases are well-understood, domain-specific models typically offer superior performance and interpretability.

8.1.1 Open Questions

Several fundamental questions remain unresolved. We do not understand if there are fundamental limits to what can be predicted, given the inherent unpredictability of chemical systems and the reliance on tacit knowledge. It remains unclear whether generative models achieve a genuine understanding of chemistry or merely excel at pattern recognition, a distinction obscured by the lack of methods to quantify chemical reasoning [Alampara et al. (2025)]. This uncertainty challenges the need for human-interpretable output, implying that the latent knowledge within hidden embeddings may be more significant [Hao et al. (2024)]. Moreover, we do not know what new datasets and techniques need to be developed, given the fact that the knowledge we extract from already published data is approaching a limit.[Silver and Sutton (n.d.)] New data most likely will be generated by agents learning from their own experience. To optimize systems, we need to better understand the underlying structure of chemical data. In many other fields, data distributions have been shaped by special driving forces. For example, evolution led to a direct link between sequence and fitness in biological sequences, which makes such datasets special. In chemistry, it is unclear what the “driving force” that shapes datasets is.

It is also unclear how quickly these innovations will permeate the average chemistry lab, where the adoption of new technology depends on more than just predictive prowess. And we also do not know yet how we should interface with those models for the greatest effectiveness. In addition, it is also unclear how far acceleration can take us, as nature imposes some natural speed limits: Some experiments simply take their time.

8.1.1.1 Looking Ahead

Overall, this landscape suggests a future rich with opportunity. And there are already some practical use cases for which we provide tutorials at https://gpmbook.lamalab.org/tutorial-literature.html. But realizing the potential impact of GPMs demands clear-eyed caution: while it is now deceptively easy to spin up prototypes, transforming them into robust, reliable tools is a far more arduous task. [Sculley et al. (2014)] More crucial still is our need for rigorous measurement and feedback—whether in the construction of evaluation suites, the calibration of reward functions for reinforcement learning, or the design of sensible governance. No single discipline can shoulder this alone; chemists, policy experts, and computer scientists must broaden their ranks and collaborate. This is particularly true since science has always benefited from embracing a diversity of approaches. While GPM-powered approaches for science, such as “AI scientists”, hold promise, a myopic focus on “AI scientists” might lead to “scientific monocultures”.[Savitsky (2025)] We hope this review lowers the barrier to entry to the background and applications of GPMs in the chemical sciences, inviting a wider spectrum of contributors to adopt a systems-science mindset—and, in doing so, to help harness the best of what GPMs can offer for tackling the chemical sciences’ most persistent and pressing challenges.