5 Applications

5.1 Automating the Scientific Workflow

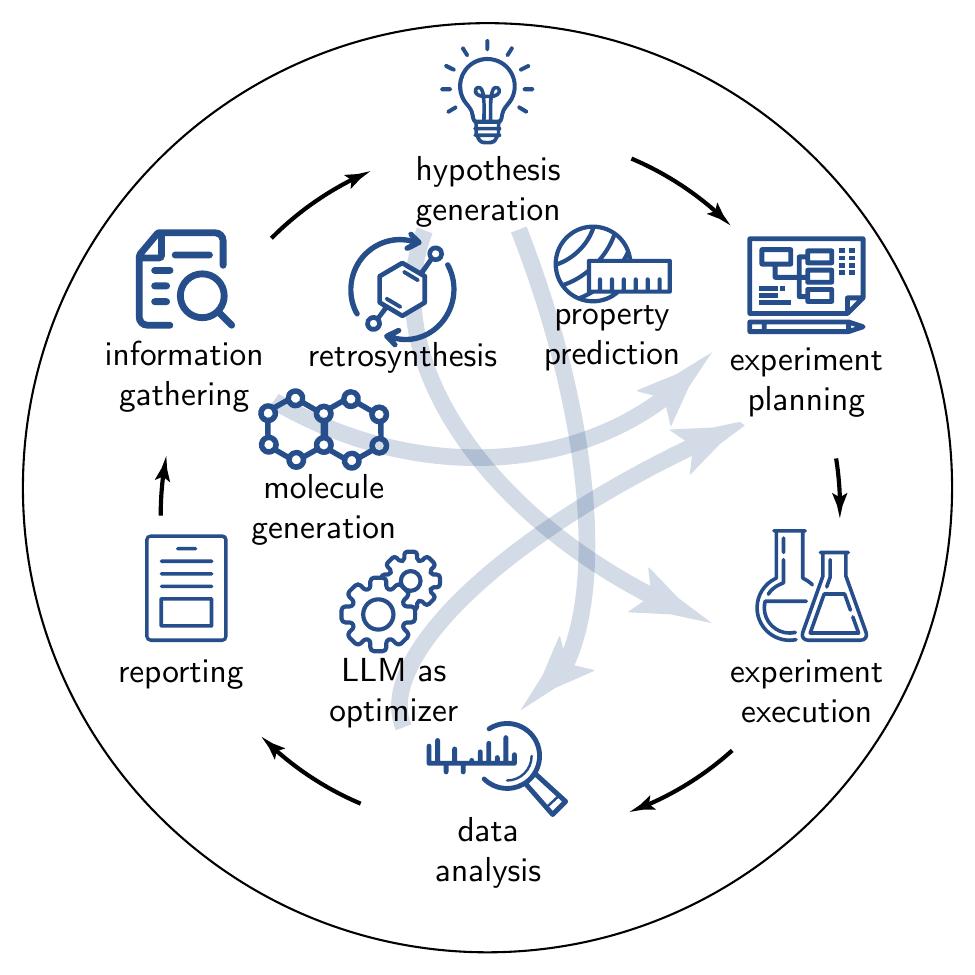

Recent advances in general-purpose model (GPM)s, particularly large language model (LLM)s, have enabled initial demonstrations of fully autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) scientists [Schmidgall et al. (2025)]. We define these as LLM-powered architectures capable of executing end-to-end research workflows based solely on the final objectives, e.g., “Unexplained rise of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas. Formulate hypotheses, design confirmatory in vitro assays, and suggest repurposing candidates for liver-fibrosis drugs”. Such systems navigate partially or entirely through all components of the scientific process outlined in Figure 5.1, and detailed in the subsequent sections.

While there are plenty of demonstrations of such systems in machine learning (ML) and programming, scientific implementations remain less explored.

5.1.1 Coding and ML Applications of AI Scientists

Frameworks such as Co-Scientist [Gottweis et al. (2025)], and AI-Scientist [Yamada et al. (2025)] aim to automate the entire ML research pipeline. They typically use multi-agent architectures (described in detail in Section 3.12.2.1) where specialized agents manage distinct phases of the scientific method [Schmidgall and Moor (2025)]. Critical to these systems is self-reflection [Renze and Guven (2024)]—iterative evaluation and criticism of results within validation loops. However, comparative analyses reveal that LLM-based evaluations frequently overscore outputs relative to human assessments [Q. Huang et al. (2023); Chan et al. (2024); Starace et al. (2025)]. An alternative is to couple these systems with evolutionary algorithms. AlphaEvolve [Novikov et al. (n.d.)] is an LLM operating within a genetic algorithm (GA) environment and discovered novel algorithms for matrix multiplication (which had remained unchanged for fifty years) and sorting.

5.1.3 Are these Systems Capable of Real Autonomous Research?

Although agents like Zochi [Intology.ai (n.d.)] achieved peer-reviewed publication in top-tier venues (association for computational linguistics (ACL) 2025), their capacity for truly autonomous end-to-end research remains debatable [Son et al. (2025)]. Even when generating hypotheses that appear novel and impactful, their execution and reporting of these ideas, as demonstrated by Si, Hashimoto, and Yang (2025), yield results deemed less attractive than those produced by humans. Additionally, while AI autonomous systems can generate hypotheses, conduct experiments, and produce publication-ready manuscripts, their integration requires careful consideration (refer to Section 7.3 for further discussion on moral concerns surrounding these systems).

5.1.4 Limitations

Despite impressive demos, current “AI scientists” systems are still hindered by fundamental limitations. Their literature synthesis is often shallow, and they have weak novelty checks, with audits of tools showing that they can misclassify familiar ideas as “new”, and generally struggle to ground claims in prior work [Beel, Kan, and Baumgart (2025)]. Execution is equally fraught; automated pipelines exhibit fragile performance, and silent errors that self-review cannot catch [Luo, Kasirzadeh, and Shah (2025)], necessitating expert oversight and validation [Gottweis et al. (2025)]. In chemistry, beyond idea generation, the hardest problems are infrastructural: closing the loop in real labs still runs into orchestration and integration headaches, heterogeneous instrument application programming interface (API)s, messy data plumbing-issues [Canty et al. (2025); Fehlis et al. (2025)], and safety and governance concerns [Leong et al. (2025)]. Finally, evaluation is immature (refer to Section 4.3.1.2 for a deeper discussion on these evaluation methods): benchmarks for autonomous agents remain narrow and inconsistent, making it hard to trust self-reported improvements or generalize beyond tightly curated demos [Yehudai et al. (2025)].

5.1.5 Open Challenges

Capability: Developing reliable long-horizon planning with verifiable execution traces [Starace et al. (2025)], evaluated on standardized, domain-grounded benchmarks [Yehudai et al. (2025)].

Evaluation Beyond LLM-as-Judge: Persistent biases and instability call for human-grounded protocols, adversarial test sets, and cross-lab replication [Thakur et al. (2024); Starace et al. (2025)].

Infrastructure: Evolving literature operations from generic retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to auditable claim-evidence graphs, contradiction mining, and robust novelty checks.

Trust & Governance: Ensuring trustworthy autonomy through calibrated uncertainty quantification and clear authorship policies aligned with scholarly norms [ACS Publications (n.d.)].

True acceleration of chemical research and the ultimate goal of fully autonomous science require AI systems that can operate across the entire scientific workflow. The stages outlined in Figure 5.1—from hypothesis generation to experimental execution and final reporting—represent the core of this process. While GPMs, especially LLMs, show promise in individual components, for AI to evolve from a showcase into a driver of fully autonomous research, it must master the entire workflow, seamlessly navigating between each of these stages.

5.2 Existing GPMs for Chemical Science

The development of GPMs for chemical science represents a departure from traditional single-task approaches. Rather than fine-tuning pre-trained models for specific tasks such as property prediction or molecular generation, these chemistry-aware models are intentionally designed to be capable of performing different chemical tasks. This multitask learning unifies related chemical tasks, boosting data efficiency and enabling emergent capabilities through joint training across domains. Table 5.1 shows an overview of the existing GPMs in the chemical sciences.

| Model | Architecture | Training | Representative Tasks | Representative Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

DARWIN 1.5 [Xie et al. (2025)] |

decoder-only transformer (LLaMA) with 7B parameters | fine-tuning on questions & answers (Q&A)s; multi-task fine-tuning on language-interfaced classification and regression tasks | materials property prediction from natural language prompts | inorganic materials |

ChemLLM [D. Zhang et al. (2024)] |

decoder-only transformer (InternLM2) with 7B parameters | instruction-tuning on template-based using supervised fine-tuning (SFT) or direct preference optimization (DPO) | multi-topic chemistry Q&A | organic molecules & reactions |

nach0 [Livne et al. (2024)] |

encoder-decoder transformer (T5) with 250M or 780M parameters | pre-trained using self-supervised learning (SSL) on scientific literature and simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) strings; instruction-tuned | natural language to SMILES; small-molecule property prediction | organic molecules & reactions |

LLaMat [Mishra et al. (2024)] |

decoder-only transformer (LLaMA) with 7B parameters | continued pre-training on materials literature and crystallographic data | materials information extraction; understanding and generating crystallographic information file (CIF)s | inorganic materials |

ChemDFM [Z. Zhao et al. (2024)] |

decoder-only transformer (LLaMA) with 13B parameters | pre-trained on 34B tokens from chemistry papers and textbooks; instruction-tuned with Q&A and SMILES | SMILES to text; molecule/reaction property prediction | organic molecules & reactions |

ether0 [Narayanan et al. (2025)] |

decoder-only transformer (Mistral-Small) with 24B parameters; mixture of experts (MoE) | SFT on reasoning traces, then reinforcement learning (RL) | molecular editing; one-step retrosynthesis; reaction prediction | organic molecules & reactions |

5.2.1 Domain Pre-Training and Multitask Learning

DARWIN 1.5 used a multitask approach to fine-tune Llama-7B through a two-stage process [Xie et al. (2025)]. In the first step, the base model was fine-tuned on \(332k\) scientific Q&A pairs to establish foundational scientific reasoning. Subsequently, the model underwent multitask learning on \(22\) different regression and classification tasks based on experimental datasets. DARWIN 1.5’s core idea is the use of language-interfaced finetuning (LIFT) (see Section 3.11) on diverse materials tasks to induce cross-task transfer during training. However, in some cases, the results revealed negative task-interaction, i.e., some tasks had diminished performance under multi-tasking.

ChemLLM followed a similar approach to DARWIN 1.5: template-based instruction tuning (ChemData) on \(~7M\) Q&A pairs. [D. Zhang et al. (2024)].

While the above examples focus on combining different in-domain tasks, nach0 coupled natural language with chemical data [Livne et al. (2024)], based on a unified encoder-decoder transformer architecture. The model was pre-trained using SSL on a combination of SMILES strings and natural language from scientific literature, and then instruction-tuned on chemistry and natural-language processing (NLP) tasks. This allows nach0 to translate between natural language and SMILES, in addition to tasks like Q&A, information extraction, and molecule/reaction generation.

LLaMat employed parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) to continue the pre-training on crystal structure data in CIF format, enabling the generation of thermodynamically stable structures [Mishra et al. (2024)].

ChemDFM scaled this concept significantly, implementing domain pre-training on over 34 billion tokens from chemical textbooks and research articles [Z. Zhao et al. (2024)]. After that, through comprehensive instruction tuning, ChemDFM familiarizes itself with chemical notation and patterns, distinguishing it from more materials-focused approaches like LLaMat through its broader chemical knowledge base.

5.2.1.1 Reasoning-Based Approaches

A recent development in chemical GPMs incorporates explicit reasoning capabilities. The ether0 model demonstrated this approach as a 24 billion-parameter reasoning model trained on over 640k chemically-verifiable problems (e.g., through code) across 375 tasks, including single-step retrosynthesis, molecular editing, and reaction prediction [Narayanan et al. (2025)]. Unlike previous models, ether0’s training used a novel RL approach (see Section 3.7). First, DeepSeek-R1 was prompted to create long chain-of-thought (CoT) traces ending in a SMILES. These traces were used to fine-tune a pre-trained Mistral-Small-24B using SFT, resulting in a “base reasoner” model. This model underwent RL using group-relative policy optimization (GRPO) on several verifiable chemical tasks to create “specialist” models—one for each task. High-quality outputs from these specialist models were selected and used to fine-tune the “base reasoner” to create a “generalist” model, capable of reasoning about all the tasks. In the last step, the generalist model undergoes another round of RL on the chemical tasks to improve the performance. This method shows that structured problem-solving approaches can significantly improve performance on complex chemical tasks without the need for massive domain-specific corpora.

These diverse approaches illustrate the evolving landscape of chemical GPMs. Still, most applications of GPMs focus on using such models for one specific application, and we will review those in the following.

5.2.2 Limitations

Chemical GPMs are emerging, but we lack systematic understanding of how to build effective ones.

The tokenization question remains unresolved. Domain-specific tokenizers might improve data efficiency, but they prevent reuse of models trained on general text datasets. The tradeoff remains unclear.

A deeper challenge exists: we might lack sufficient high-quality data. Existing chemical datasets are much smaller than those used in domains like mathematics Chapter 2. The literature reports only successes. Failed experiments, discarded results, and negative outcomes never appear in published datasets. More critically, chemical practitioners rely on tacit knowledge[Polanyi (2009)]—expertise acquired through experience that experts cannot fully articulate. This implicit understanding remains absent from existing datasets.

5.3 Knowledge Gathering

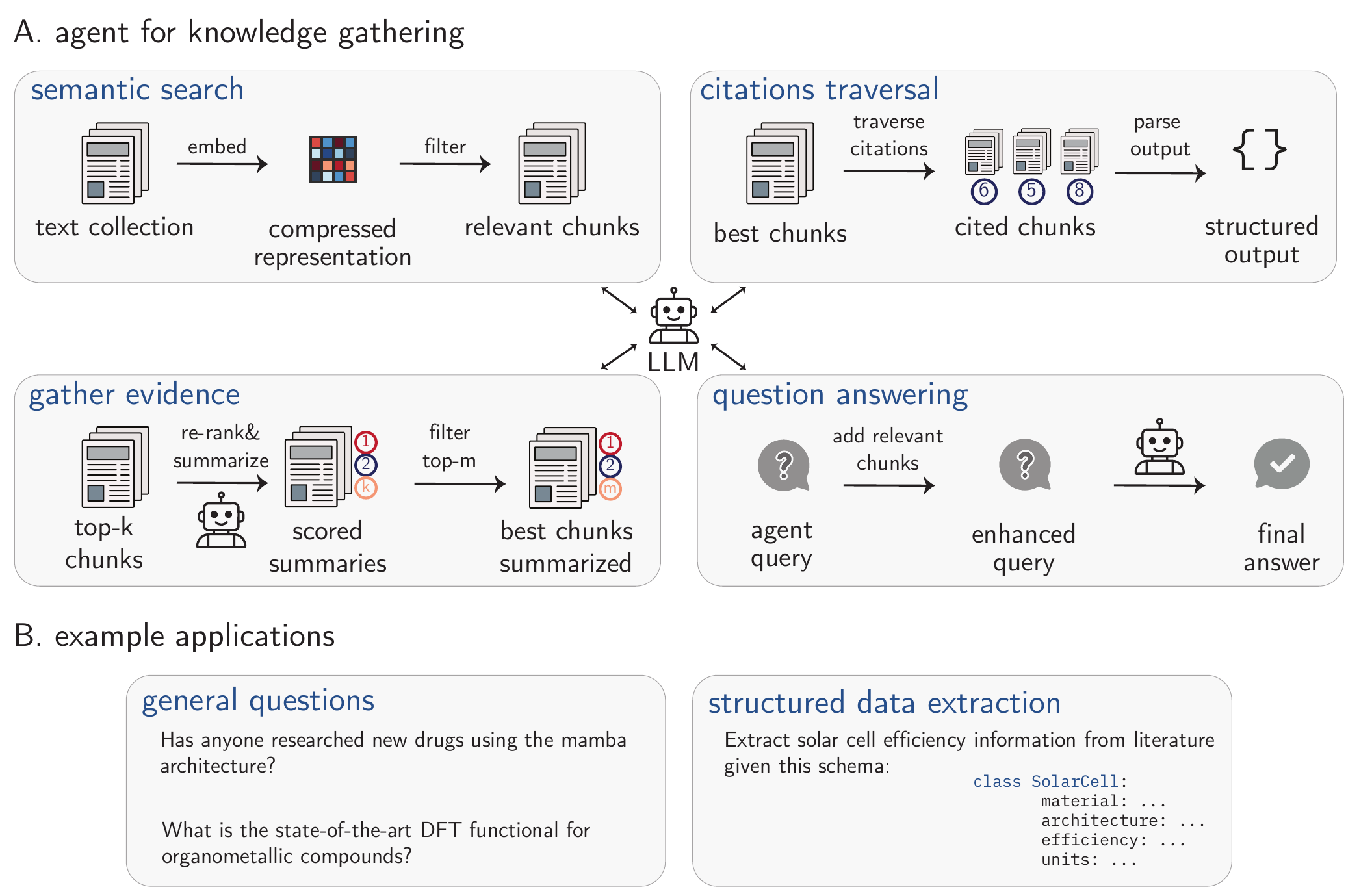

The rate of publishing keeps growing, and as a result, it is increasingly challenging to manually collect all relevant knowledge, potentially stymying scientific progress.[Schilling-Wilhelmi et al. (2025); Chu and Evans (2021)] Even though knowledge collection might seem like a simple task, it often involves multiple steps, visually described in Figure 5.2 A. Here, we focus on structured data extraction and question answering. Example queries for both sections are in Figure 5.2 B.

5.3.1 Semantic Search

A step that is key to most, if not all, knowledge-gathering tasks is RAG, discussed in more detail in Section 3.12.1.3. Most commonly, this involves semantic search, intended to identify chunks of text with similar meaning. The difference between semantic search and conventional search lies in how each approach interprets queries. The latter operates through lexical matching—whether exact or fuzzy—focusing on the literal words and their variations. Semantic search, however, focuses on the underlying meaning and contextual relationships within the content.

To enable semantic search, documents are converted into embeddings (see Section 3.2.3) [Bojanowski et al. (2017)]. They allow for similarity search by vector comparison (e.g., using cosine similarity for small databases or more sophisticated algorithms like hierarchical navigable small world (HNSW) for large databases[Malkov and Yashunin (2018)]).

In chemistry, semantic search has been used extensively to classify and identify chemical text.[Guo et al. (2021); Beltagy, Lo, and Cohan (2019); Trewartha et al. (2022)]

PaperQA2 agent.(M. D. Skarlinski et al. 2024) B. Two examples of applications are discussed in this section. C. Worked example using the FutureHouse’s platform (the Crow agent). “Used in 1.1” indicates that this reference has been used in the final response of the model(M. Skarlinski et al. 2025).

5.3.2 Structured Data Extraction

For many applications, it can be useful to collect data in a structured form, e.g., tables with fixed columns. Obtaining such a dataset by extracting data from the literature using LLMs is currently one of the most practical avenues for LLMs in the chemical sciences [Schilling-Wilhelmi et al. (2025)].

5.3.2.1 Data Extraction Using Prompting

For most applications, zero-shot prompting should be the starting point. Zero-shot prompting has been used to extract data about organic reactions[Rı́os-Garcı́a and Jablonka (2025); Vangala et al. (2024); Patiny and Godin (2023)], synthesis procedures for metal-organic frameworks[Zheng et al. (2023)], polymer data[Schilling-Wilhelmi and Jablonka (2024); S. Gupta et al. (2024)], or other materials data[Polak and Morgan (2024); Hira et al. (2024); Kumar, Kabra, and Cole (2025); Wu et al. (2025); S. Huang and Cole (2022)].

5.3.2.2 Fine-tuning Based Data Extraction

If a (commercial) model needs to be run very often, it can be more cost-efficient to fine-tune a smaller, open-source model compared to prompting a large model (see Section 3.10.4). In addition, models might lack specialized knowledge and might not follow certain style guides, which can be introduced with fine-tuning. Ai et al. (2024) fine-tuned the LLaMa-2-7B model to extract chemical reaction data from United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) into a JavaScript object notation (JSON) format compatible with the schema of Open Reaction Database (ORD)[Kearnes et al. (2021)], achieving an overall accuracy of more than \(90\%\). In a different approach, W. Zhang et al. (2024) fine-tuned a closed-source model — GPT-3.5-Turbo to recognize and extract chemical entities from USPTO. Fine-tuning improved the performance of the base model on the same task by more than \(15\%\). Dagdelen et al. (2024) went beyond the afore-mentioned methods by using a human-in-the-loop data annotation process. Here, humans corrected the outputs from an LLM extraction instead of annotating data from scratch.

5.3.2.3 Agents for Data Extraction

Agents (Section 3.12) have shown their potential in data extraction, though to a limited extent.[K. Chen et al. (2024); Kang and Kim (2024)] For example, Ansari and Moosavi (2024) introduced Eunomia, an agent that autonomously extracts structured materials data from scientific literature without requiring fine-tuning. Their agent is an LLM with access to tools such as chemical databases (e.g., the Materials Project database) and research papers from various sources. The document search tool leverages an API-based embedding model to find the top-k most relevant passages based on semantic similarity. Other tools used include the chain-of-verification tool, which queries the agent independently (to avoid bias) in order to generate verification queries and finally produces a verified response.

While the authors claim this approach simplifies dataset creation for materials discovery, the evaluation is limited to a narrow set of materials science tasks (mostly focusing on metal-organic framework (MOF)s), indicating the need for the creation of agent evaluation tools.

5.3.3 Question Answering

Besides extracting information from documents in a structured format, LLMs can also be used to answer questions—such as “Has X been tried before” by synthesizing knowledge from a corpus of documents (and potentially automatically retrieving additional documents).

An example of a system that can do that is PaperQA. This agentic system contains tools for search, evidence-gathering, and question answering as well as for traversing citation graphs, which are shown in Figure 5.2. The evidence-gathering tool collects the most relevant chunks of information via the semantic search and performs LLM-based re-ranking of these chunks (i.e., the LLM changes the order of the chunks depending on what is needed to answer the query). Subsequently, only the top-\(n\) most relevant chunks are kept. To further ground the responses, citation traversal tools (e.g., Semantic Scholar[Kinney et al. (2023)]) are used. These leverage the citation graph as a means of discovering supplementary literature references. Ultimately, to address the user’s query, a question-answering tool (a specially prompted LLM) is employed. It initially augments the query with all the collected information before providing a definitive answer. The knowledge aggregated by these systems could be used to generate new hypotheses or challenge existing ones.

5.3.4 Limitations

LLMs and LLM-based systems are valuable information-gathering tools, but they have critical limitations. Their knowledge becomes outdated immediately after training. Without additional tools, they cannot identify when retrieved sources have been retracted or corrected.

Effective knowledge gathering requires human-AI collaboration. Current systems struggle to ask relevant clarifying questions.[Choudhury et al. (2025)] Domain-specific benchmarks for evaluating this capability remain absent, hindering progress in developing truly interactive knowledge-gathering agents.

5.3.5 Open Challenges

Critical challenges remain unresolved:

Multimodal Understanding. Current models cannot reliably extract data from plots, tables, and figures.[Alampara, Schilling-Wilhelmi, et al. (2025); T. Gupta et al. (2022)] This severely limits data extraction because substantial chemical knowledge exists only in visual formats. Improved multimodal capabilities are essential for comprehensive literature mining.

Source Quality Assessment. Selecting high-quality sources, that are also relevant to the scientific query, remains an open challenge, with scholarly metrics alone being insufficient.

5.4 Hypothesis Generation

Coming up with new hypotheses represents a cornerstone of the scientific process [Rock (n.d.)]. Historically, hypotheses have emerged from systematic observation of natural phenomena, exemplified by Isaac Newton’s formulation of the law of universal gravitation [Newton (1999)], which was inspired by the seemingly mundane observation of a falling apple [Kosso (2017)].

In modern research, hypothesis generation increasingly relies on data-driven tools. For example, clinical research employs frameworks such as visual interactive analytic tool for filtering and summarizing large health data sets (VIADS) to derive testable hypotheses from well-curated datasets [Jing et al. (2022)]. Similarly, advances in LLMs are now being explored for their potential to automate and enhance idea generation across scientific domains [O’Neill et al. (2025)]. However, such approaches face significant challenges due to the inherently open-ended nature of scientific discovery [Stanley, Lehman, and Soros (2017)]. Open-ended domains, as discussed in Chapter 2, risk intractability, as an unbounded combinatorial space of potential variables, interactions, and experimental parameters complicates systematic exploration [Clune (2019)]. Moreover, the quantitative evaluation of the novelty and impact of generated hypotheses remains non-trivial. As Karl Popper argued, scientific discovery defies rigid logical frameworks [Popper (1959)], and objective metrics for “greatness” of ideas are elusive [Stanley and Lehman (2015)]. These challenges underscore the complexity of automating or systematizing the creative core of scientific inquiry.

5.4.1 Initial Sparks

Recent efforts in the ML community have sought to simulate the hypothesis formulation process [Gu and Krenn (2025); Arlt et al. (2024)], primarily leveraging multi-agent systems [Jansen et al. (2025); Kumbhar et al. (2025)]. In such frameworks, agents typically retrieve prior knowledge to contextualize previous related work, grounding hypothesis generation in existing literature [Naumov et al. (2025); Ghareeb et al. (2025); Gu and Krenn (2024)]. A key challenge, however, lies in evaluating the generated hypotheses. While some studies leverage LLMs to evaluate novelty or interestingness [J. Zhang et al. (2024)], recent work has introduced critic agents—specialized components designed to monitor and iteratively correct outputs from other agents—into multi-agent frameworks (see Section 3.12.2.1). For instance, Ghafarollahi and Buehler (2024) demonstrated how integrating such critics enables systematic hypothesis refinement through continuous feedback mechanisms.

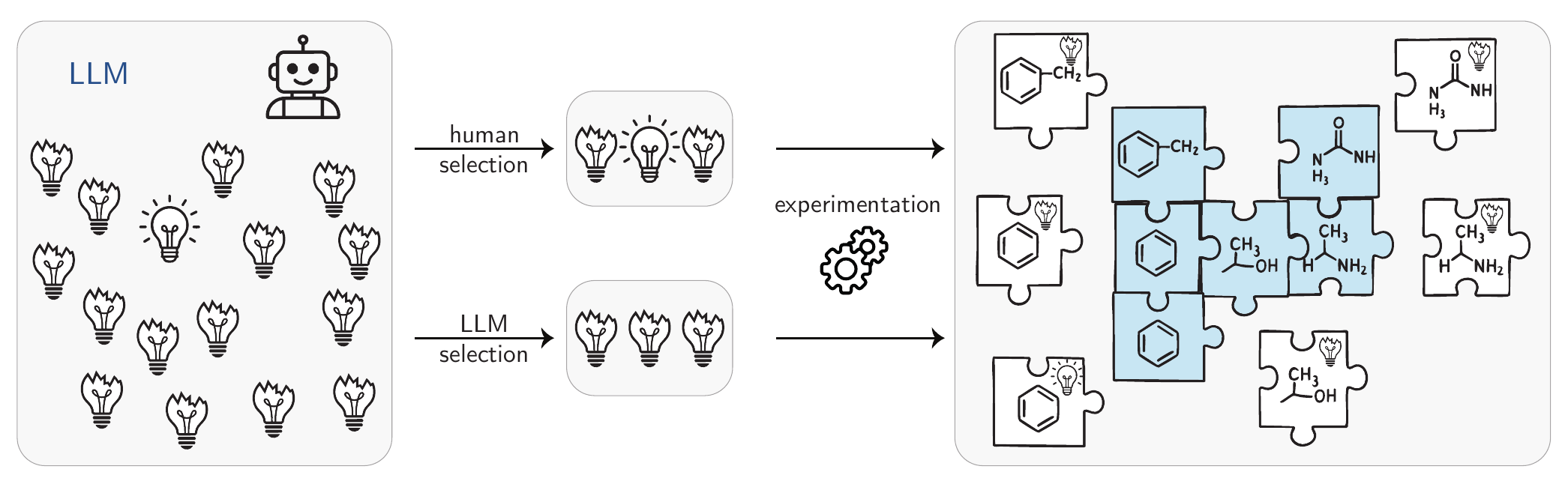

However, the reliability of purely model-based evaluation remains contentious. Si, Yang, and Hashimoto (2025) argued that relying on a LLM to evaluate hypotheses lacks robustness, advocating instead for human assessment. This approach was adopted in their work, where human evaluators validated hypotheses produced by their system, finding more novel LLM-produced hypotheses compared to the ones proposed by humans. Notably, Yamada et al. (2025) advanced the scope of such systems by automating the entire research ML process, from hypothesis generation to article writing. Their system’s outputs were submitted to workshops at the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2025, with one contribution ultimately accepted. However, the advancements made by such works are currently incremental instead of unveiling new, paradigm-shifting research (see Figure 5.3).

5.4.2 Chemistry-Focused Hypotheses

In chemistry and materials science, hypothesis generation requires domain intuition, mastery of specialized terminology, and the ability to reason through foundational concepts [Miret and Krishnan (2024)]. To address potential knowledge gaps in LLMs, Q. Wang et al. (2023) proposed a few-shot learning approach (see Section 3.11.1) for hypothesis generation and compared it with model fine-tuning for the same task. Their method strategically incorporates in-context examples to supplement domain knowledge while discouraging over-reliance on existing literature. For fine-tuning, they designed a loss function that penalizes possible biases—e.g., given the context “hierarchical tables challenge numerical reasoning”, the model would be penalized if it generated an overly generic prediction like “table analysis” instead of a task-specific one—when trained on such examples. Human evaluations of ablation studies revealed that GPT-4, augmented with a knowledge graph of prior research, outperformed fine-tuned models in generating hypotheses with greater technical specificity and iterative refinement of such hypotheses.

Complementing this work, Yang, Liu, Gao, Xie, et al. (2025) introduced the Moose-Chem framework to evaluate the novelty of LLM-generated hypotheses. To avoid data contamination, their benchmark exclusively uses papers published after the knowledge cutoff date of the evaluated model, GPT-4o. Ground-truth hypotheses were derived from articles in high-impact journals (e.g., Nature, Science) and validated by domain-specialized PhD researchers. By iteratively providing the model with context from prior studies, GPT-4o achieved coverage of over \(80\%\) of the evaluation set’s hypotheses while accessing only \(4\%\) of the retrieval corpus, demonstrating efficient synthesis of ideas presumably not present in its training corpus.

5.4.3 Are LLMs Actually Capable of Novel Hypothesis Generation?

Automatic hypothesis generation is often regarded as the Holy Grail of automating the scientific process [Coley, Eyke, and Jensen (2020)]. However, achieving this milestone remains challenging, as generating novel and impactful ideas requires questioning current scientific paradigms [Kuhn (1962)]—a skill typically refined through years of experience—which is currently impossible for most ML systems.

Current progress in ML illustrates these limitations [Kon et al. (2025); Gu and Krenn (2024)]. Although some studies claim success, as AI-generated ideas being accepted at workshops in ML conferences via double-blind review [Zhou and Arel (2025)], these achievements are limited. First, accepted submissions often focus on coding tasks, one of the strongest domains for LLMs. Second, workshop acceptances are less competitive than main conferences, as they prioritize early-stage ideas over rigorously validated contributions. In chemistry, despite some works showing promise on these systems [Yang, Liu, Gao, Liu, et al. (2025)], LLMs struggle to propose innovative hypotheses [Si, Hashimoto, and Yang (2025)]. Their apparent success often hinges on extensive sampling and iterative refinement, rather than genuine conceptual innovation.

As Kuhn (1962) argued, generating groundbreaking ideas demands challenging prevailing paradigms—a capability missing in current ML models (they are trained to make the existing paradigm more likely in training rather than questioning their training data), as shown in Figure 5.3. Thus, while accidental discoveries can arise from non-programmed events (e.g., Fleming’s identification of penicillin [Fleming (1929); Fleming (n.d.)]), transformative scientific advances typically originate from deliberate critique of existing knowledge [Popper (1959); Lakatos (1970)]. In addition, very often breakthroughs can not be achieved by optimizing for a simple metric—as we often do not fully understand the problem and, hence, cannot design a metric.[Stanley and Lehman (2015)] Despite some publications suggesting that AI scientists already exist, such claims are supported only by narrow evaluations that yield incremental progress [Novikov et al. (n.d.)], not paradigm-shifting insights. For AI to evolve from research assistants into autonomous scientists, it must demonstrate efficacy in addressing societally consequential challenges, such as solving complex, open-ended problems at scale (e.g., “millennium” math problems [Carlson, Jaffe, and Wiles (2006)]).

Finally, ethical considerations become critical as hypothesis generation grows more data-driven and automated. Adherence to legal and ethical standards must guide these efforts (see Section 7.2)[The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics (n.d.)].

5.4.4 Limitations

Current LLM-driven systems lack the kind of creativity needed for paradigm-shifting hypotheses, tending to rearrange training data and retrieved content rather than propose genuinely new mechanisms. As a result, the evaluation of such outputs is also fragile, because using proxy metrics for “novelty” or “impact” that poorly track real scientific value can be deceiving. Finally, the problem’s open-ended nature (Chapter 4) makes systematic benchmarking ill-posed.

5.4.5 Open Challenges

Scalable Evaluation: The open-ended assessment of a hypothesis’s potential impact remains a core challenge, as current methods are difficult to scale, costly, and inefficient due to a heavy reliance on human input [Nie et al. (2025)].

The Integration Gap: A critical disconnect persists between hypothesis generation and automated experimental validation, especially in fields like chemistry.

The Paradigm Limitation: The underlying operational constraints of current modeling approaches inherently favor incremental progress over transformative breakthroughs.

5.5 Experiment Planning

Before a human or robot can execute any experiments, a plan must be created. Planning can be formalized as the process of decomposing a high-level task into a structured sequence of actionable steps aimed at achieving a specific goal. The term planning is often confused with scheduling and RL, which are closely related but distinct concepts. Scheduling is a more specific process focused on the timing and sequence of tasks. It ensures that resources are efficiently allocated, experiments are conducted in an optimal order, and constraints (such as lab availability, time, and equipment) are respected.[Kambhampati et al. (n.d.)] RL is about adapting and improving plans over time based on ongoing results.[P. Chen et al. (2022)]

5.5.1 Conventional Planning

Early chemical planning systems, such as logic and heuristics applied to synthetic analysis (LHASA) [Corey, Cramer III, and Howe (1972)] and Chematica[Grzybowski et al. (2018)], relied on simple rules and templates. In particular, Chematica used heuristic-guided graph search with rule-based transforms and scoring functions to prune and prioritize routes. Modern systems, like ASKCOS[Tu et al. (2025)], explicitly use search algorithms such as breadth-first search (BFS) or Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS)[Segler, Preuß, and Waller (2017)] to explore the combinatorially large space. But these planning search algorithms remain inefficient for long-horizon or complex planning tasks. [X. Liu et al. (2024); D. Zhao, Tu, and Xu (2024)]

5.5.2 LLMs to Decompose Problems into Plans

GPMs, in particular LLMs, can potentially assist in planning with two modes of thinking. Deliberate thinking can be used to score potential options or to decompose problems into plans. Intuitive thinking can be used to efficiently prune search spaces. These two modes align with psychological frameworks known as system-1 (intuitive) and system-2 (deliberate) thinking. [Kahneman (2011)] In the system-1 thinking, LLMs support rapid decision-making by leveraging heuristics and pattern recognition to quickly narrow down options. In contrast, system-2 thinking represents a slower, more analytical process, in which LLMs solve complex tasks by explicitly generating step-by-step reasoning. [Ji et al. (2025)]

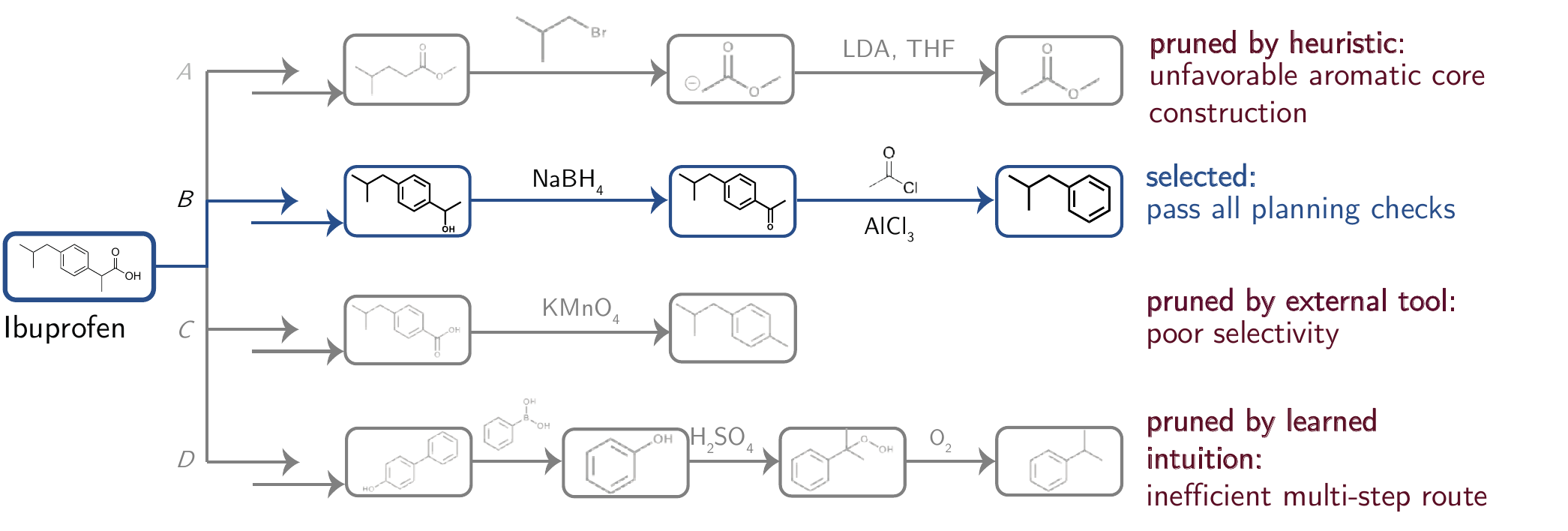

Figure 5.4 shows how an LLM applies this deliberate, system-2-style reasoning to decompose a chemical problem into a sequence of planned steps. A variety of strategies have been proposed to improve the reasoning capabilities of LLMs during inference. Methods such as CoT and least-to-most prompting guide models to decompose. However, their effectiveness in planning is limited by error accumulation and linear thinking patterns.[Stechly, Valmeekam, and Kambhampati (2024)] To address these limitations, recent test-time strategies such as repeat sampling and tree search have been proposed. Repeated sampling allows the model to generate multiple candidate reasoning paths, encouraging diversity in thought and increasing the chances of discovering effective subgoal decompositions. [E. Wang et al. (2024)] Meanwhile, tree search methods like tree-of-thought (ToT) and reasoning via planning (RAP) treat reasoning as a structured search, using algorithms like MCTS to explore and evaluate multiple solution paths, facilitating more global and strategic decision-making. [Hao et al. (2023)]

LLMs have also been applied to generate structured procedures from limited observations. For example, in quantum physics, a model was trained to infer reusable experimental templates from measurement data, producing Python code that generalized across system sizes. [Arlt et al. (2024)]

5.5.3 Pruning of Search Spaces

Pruning refers to the process of eliminating unlikely or suboptimal options during the search to reduce the computational burden. Classical planners employ heuristics, value functions, or logical filters to perform pruning[Bonet and Geffner (2012)].

Figure 5.5 illustrates how LLMs can support experimental planning by pruning options by emulating an expert chemist’s intuition by discarding synthetic routes that appear unnecessarily long, inefficient, or mechanistically implausible.

To further enhance planning efficacy, LLMs can be augmented with external tools that estimate the feasibility or performance of candidate plans, enabling targeted pruning of the search space before costly execution.

Beyond external tools, LLMs can self-correct by pruning flawed reasoning steps to produce more coherent plans. At a higher level of oversight, human-in-the-loop frameworks such as ORGANA[Darvish et al. (2025)] incorporate expert chemist feedback to refine goals, resolve ambiguities, and eliminate invalid directions. Example at Note 5.1 presents examples illustrating how planning extends to real laboratory practice.

5.5.4 Limitations

Figure 5.4 demonstrates how LLMs can generate sophisticated-looking plans that conceal critical flaws, making complex, long-horizon chemical planning tasks particularly difficult to execute reliably [Cao et al. (2025)]. A limitation is that they often produce outputs that appear chemically plausible but are invalid or unsafe, due to their optimization for linguistic plausibility rather than chemical correctness and their lack of mechanistic understanding[Andrés M. Bran and Schwaller (2024); Evans et al. (2021)] Second, errors can also propagate from external tools like retrosynthesis planners, whose data and algorithmic shortcomings constrain reliability [Z. Li et al. (2025)]. Finally, a broader limitation is the lack of grounding in experimental feedback, which creates persistent gaps between theoretical planning and practical feasibility.

5.5.5 Open Challenges

Reasoning Complexity Beyond Knowledge Retrieval: Complex chemistry problems require long, tightly interconnected chains of reasoning, where minor errors can cascade and require understanding of dynamic interactions such as temperature effects on molecular behavior. Current LLMs lack effective reasoning structures to guide domain-specific reasoning. [Ouyang et al. (2023); Tang et al. (2025)]

Evaluation and Feedback Bottleneck: Current evaluation methods are often performed manually or indirectly, either relying on expert review as in

ChemCrow[Andres M. Bran et al. (2024)] or on pseudocode-based comparisons as inBioPlanner.[O’Donoghue et al. (2023)] Integrating feedback remains an open direction for improving the practical feasibility of generated plans.

5.6 Experiment Execution

Once an experimental plan is available, whether from a human scientist’s idea or an AI model, the next step is to execute it. Regardless of its source, the plan must be translated into concrete, low-level actions for execution.

It is worth noting that, despite their methodological differences, executing experiments in silico (running simulations or code) and in vitro are not fundamentally different—both follow an essentially identical workflow: Plan \(\rightarrow\) Instructions \(\rightarrow\) Execution \(\rightarrow\) Analysis.

The execution of in silico experiments can be reduced to two essential steps: preparing input files and running the computational code; GPMs can be used in both steps.[Z. Liu, Chai, and Li (2025); Mendible-Barreto et al. (2025); Zou et al. (2025); Campbell et al. (2025)] Jacobs and Pollice (2025) found that using a combination of fine-tuning, CoT and RAG (see Section 3.11) can improve the performance of LLMs in generating executable input files for the quantum chemistry software ORCA[Neese (2022)], while Gadde et al. (2025) created AutosolvateWeb, an LLM-based platform that assists users in preparing input files for quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations of explicitly solvated molecules and running them on a remote computer. Examples of LLM-based autonomous agents (see Section 3.12) capable of performing the entire computational workflow (i.e., preparing inputs, executing the code, and analyzing the results) are MDCrow [Campbell et al. (2025)] (for molecular dynamics) and El Agente Q [Zou et al. (2025)] (for quantum chemistry).

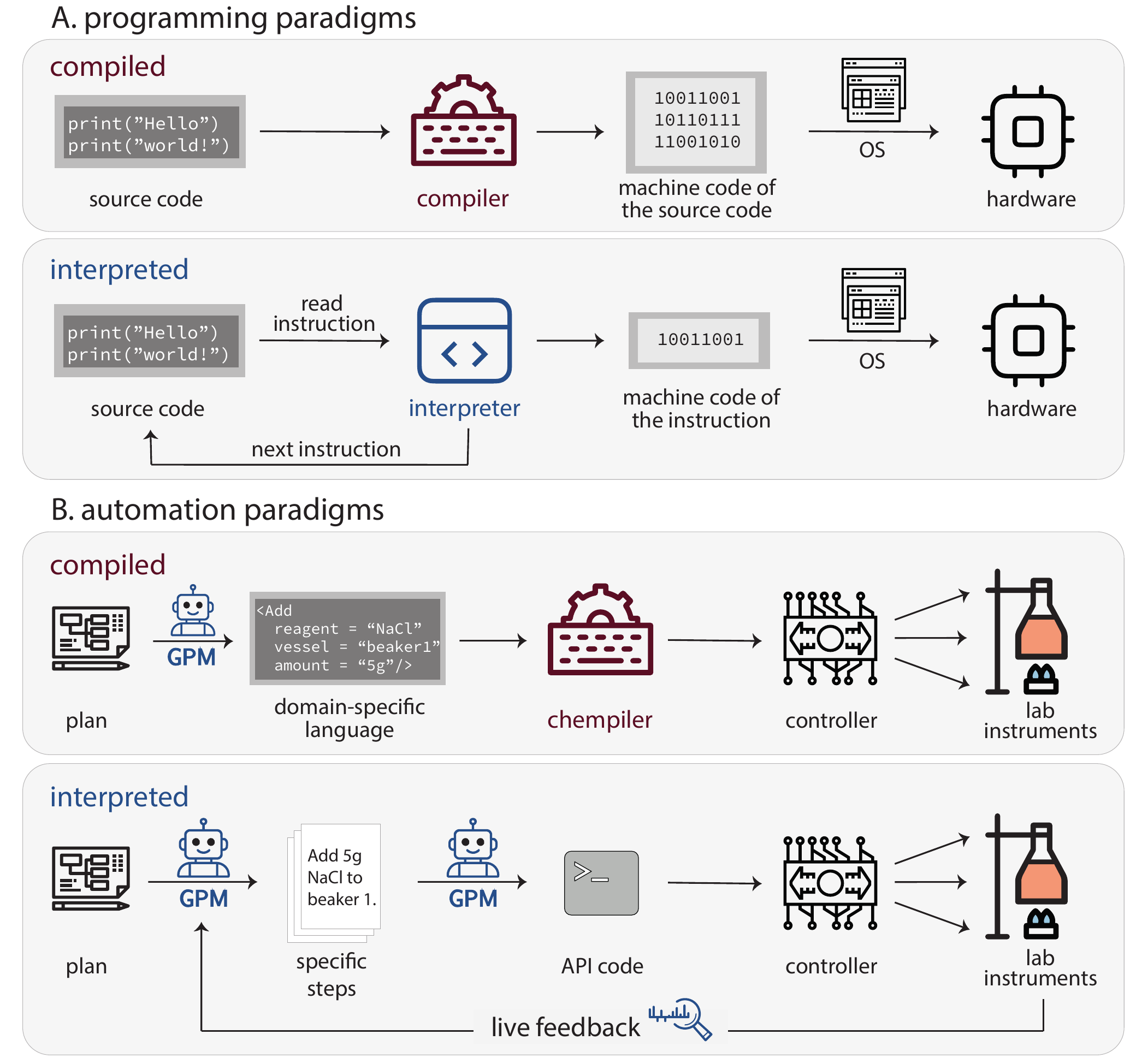

Emerging examples show GPMs assisting in in vitro experiment automation. Programming language paradigms—compiled vs. interpreted (Figure 5.6 A)—provide a useful analogy for understanding different automation approaches.

Compiled languages (C++, Fortran) convert entire programs to machine code before execution. Interpreted languages (Python, JavaScript) translate and execute instructions line-by-line at runtime. The tradeoff is that compiled languages offer higher performance and early error detection but require separate compilation steps. Interpreted languages enable rapid development and on-the-fly modification, but run slower and catch errors only during execution.

Similarly, experiment automation follows two paradigms (Figure 5.6 B): “compiled automation” translates entire protocols—by human or GPM—into low-level instructions before execution. “Interpreted automation” uses the GPM as runtime interpreter, executing protocols step-by-step.

5.6.1 Compiled Automation

In “compiled automation”, protocols are formalized in high-level languages or domain-specific language (DSL)s. A chemical compiler (“chempiler”[Mehr et al. (2020)]) converts these into low-level hardware instructions, which robotic instruments then execute (Figure 5.6 B).

While Python scripts serve as the de facto protocol language, specialized DSLs provide more structured representations.[Z. Wang et al. (2022); Ananthanarayanan and Thies (2010); Strateos (n.d.); Park et al. (2023)] For example, χDL[Mehr et al. (2020); Group (n.d.)] describes protocols using abstract commands (Add, Stir, Filter) and chemical objects (Reagents, Vessels). The Chempiler translates χDL scripts into platform-specific instructions based on the physical laboratory configuration.

Writing protocols in formal languages requires coding expertise. Here, GPMs translate natural-language protocols into machine-readable formats.[Sardiña, García-González, and Luaces (2024); Jiang et al. (2024); Conrad et al. (2025); Inagaki et al. (2023); Vaucher et al. (2020)] Pagel, Jirásek, and Cronin (2024) introduced a multi-agent workflow (based on GPT-4) that can convert unstructured chemistry papers into executable code. The first agent extracts all synthesis-relevant text, including supporting information; a procedure agent then sanitizes the data and tries to fill the gaps from chemical databases (using RAG); another agent translates procedures into χDL and simulates them on virtual hardware; finally, a critique agent cross-checks the translation and fixes errors.

The example above shows one of the strengths of the compiled approach: it allows for pre-validation. The protocol can be simulated or checked for any errors before running on the actual hardware, ensuring safety. Another example of LLM-based validators for chemistry protocols is CLAIRify.[Yoshikawa et al. (2023)] Leveraging an iterative prompting strategy, it uses GPT-3.5 to first translate the natural-language protocol into a χDL script, then automatically verifies its syntax and structure, identifies any errors, appends those errors to the prompt, and prompts the LLM again—iterating this process until a valid χDL script is produced.

5.6.2 Interpreted Automation

Interpreted programming languages support higher abstraction levels through flexible command structures. Similarly, GPMs can translate high-level goals into concrete steps,[Ahn et al. (2022); W. Huang et al. (2022)] acting as “interpreters” between experimental intent and lab hardware.

For example, given “titrate the solution until it turns purple”, a GPM agent Section 3.12 can break this into executable steps at runtime: add titrant incrementally, read color sensor, loop until condition met. This is “interpreted automation”—conversion happens during execution, not before.

The key advantage is real-time decision-making. After each action, the system analyzes sensor data (readings, spectra, errors) and selects the next step. This enables dynamic branching and conditional logic impossible in pre-compiled protocols.

Coscientist[Boiko et al. (2023)] demonstrates interpreted automation using GPT-4 to control liquid-handling robots. The system searches the web for protocols, reads instrument documentation, writes Python code in real-time, and executes experiments on physical hardware. When errors occur, GPT-4 debugs its own code. Coscientist successfully optimized palladium cross-coupling reactions, outperforming Bayesian optimization in finding high-yield conditions.

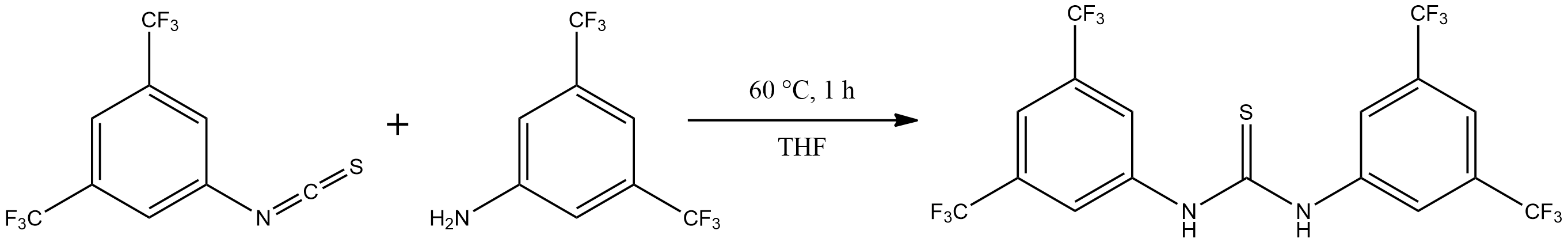

ChemCrow[Andres M. Bran et al. (2024)] augments GPT-4 with \(18\) expert-designed tools for tasks including compound lookup, spectral analysis, and retrosynthesis. It planned and executed syntheses of N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) and three thiourea organocatalysts (Note 5.1), and collaborated with chemists to discover a new chromophore.

5.6.3 Hybrid Approaches

Between fully compiled and fully interpreted automation lies a hybrid approach that combines the safety and reliability of compiled protocols with the AI-driven flexibility of interpreted systems. Each experiment run follows a fixed plan for safety and reproducibility, but between runs, the plan can adapt based on the GPM’s interpretation of results. This design provides a safeguard against interpreter errors, since every generated procedure passes through formal verification before execution—catching issues like a hallucinated instruction to add 1000 mL of solvent to a 100 mL flask.

ORGANA [Darvish et al. (2025)] is an LLM-based robotic assistant following this hybrid paradigm. It allows human chemists to describe their experimental goal in natural language. The system can converse with the user to clarify ambiguous requests (the agent would ask “do you mean X or Y?” if the instructions are unclear). Once the goal is understood, it uses CLAIRify [Yoshikawa et al. (2023)] to convert and validate the natural-language description of a chemistry experiment into a χDL script, which can be executed on a compatible platform. In one case, ORGANA carried out a multistep electrochemistry procedure—polishing electrodes, running an experiment, and analyzing the data—involving 19 substeps that it coordinated in parallel (see Note 5.1). If an unexpected observation occurred (e.g., a solution does not change color when expected), the system can notice via image analysis and modify the plan or alert the user. In user studies, ORGANA reduced the manual labor and frustration for chemists, who could offload tedious tasks and trust the agent to handle low-level decisions.

ChemCrow: When prompted with the task “Find and synthesize a thiourea organocatalyst which accelerates a Diels-Alder reaction”, ChemCrow sequentially queried tools to gather information and solve the task:

“First, I need to find a thiourea organocatalyst that can accelerate the Diels-Alder reaction. I will perform a websearch to find a suitable catalyst.

WebSearch tool: Schreiner’s thiourea catalyst

Now I will obtain the SMILES.

Name2Smiles tool:

FC(F)(F)c1cc(CN(=S)Nc2cc(C(F)(F)F)cc(C(F)(F)F)c2)cc(C(F)(F)F)c1

I will plan a synthesis for Schreiner’s thiourea catalyst.

SynthesisPlanner tool: Detailed synthesis plan

I will execute the synthesis.

SynthesisExecuter tool: Successful synthesis.”

The agent proposed to synthesize the target molecule from the corresponding isothiocyanate and aniline derivatives and executed the synthesis on the RoboRXN platform. [“RoboRXN” (n.d.)] The product was confirmed using HPLC/MS: m/z 501 [M+H] calculated, found m/z 501.02.

ORGANA: ORGANA interacts with chemists using LLMs to derive experiment goals and makes decisions with chemists in the loop to control robots and lab devices.

Start-up: Users give their intention , and start interact with

ORGANA:ORGANA: What is the setup of the lab environment? What hardware and reagents are present?User: I have a 2mM solution of the quinone……

ORGANA: Can you provide an example of how to run the experiment?User: Add 2mL of quinone……

ORGANA: What is the expected outcome of the example experiment?User: The pH of the solution is expected ……

ORGANA: How many experiments are we planning to run in total?User: 6

ORGANA: Ok, thank you! I will start the experiment……Ambiguity and Uncertainty Mitigation:

ORGANA.Reasonerevaluates whether experiment outcomes align with user expectations. If it can’t interpret the results, it alerts the user to check for environmental issues. The user provides feedback explaining the outcomes, whichORGANA.Reasonerthen uses to refine its next plan:“I’m not sure what happened, but repeat the previous experiment just in case”

“Nothing is wrong, carry on”

“The pump was stuck, it’s ok again”

Experimental Reports:

ORGANAreports the experimental logs and summaries:“A series of experiments was conducted to measure the potential of a quinone solution at various pH levels, specifically from pH 7 to pH 9… After performing the experiments, these are the results: The estimate for pKa1 is 8.096. The estimate for pKa2 is 12.380. The estimate for slope is -60.958.”

Results Comparison with Chemists: Comparison of Pourbaix diagrams and first-region slope estimates from electrochemical experiments, with

ORGANAusing three measurement points per pH region and chemists using four.ORGANAyields results comparable to those of chemists: for pKa1,ORGANAproduces 8.03 and chemists 8.02 and for the estimated slope,ORGANAobtained -61.3mV/pH while chemists obtained -62.7mV/pH.

5.6.4 Limitations

Current automation systems remain prototypes.

Interpreted systems require frequent human intervention despite autonomy claims. They replicate known procedures but lack mechanistic understanding. Non-deterministic GPM responses create reproducibility issues—small prompt changes yield different results, and closed-source models evolve unpredictably. Hallucinations risk incorrect planning for complex reactions. Hardware control introduces safety concerns: flexible GPMs can devise unanticipated actions, requiring robust safeguards (Section 7.2).

Compiled systems offer reliability but require extensive upfront formalization. The effort to translate protocols into formal languages often outweighs automation benefits for typical laboratory workflows.

5.6.5 Open Challenges

Self-driving laboratories orchestrated by GPMs face technical challenges requiring research advances:[Tom et al. (2024); Seifrid et al. (2022)]

Grounding Natural Language to Laboratory Actions. Translating ambiguous natural-language instructions (“heat gently”) into precise, safe operations requires developing validation layers that detect physically impossible or hazardous actions before hardware execution.

Universal Protocol Standards. No widely adopted formalization standard exists. While languages like χDL show promise, achieving interoperability across platforms requires community consensus on abstraction levels and device interfaces. model context protocol (MCP)s offer a potential path forward by enforcing consistent interfaces between GPMs, instruments, and verification layers.

Autonomous Error Recovery. Current systems cannot autonomously diagnose and recover from experimental failures. Developing general-purpose failure detection mechanisms and recovery strategies would enable truly autonomous operation.

Multimodal Integration. Chemists use diverse data types—spectra, chromatograms, TLC plates, and microscopy images. Integrating these modalities into GPM decision-making loops remains technically challenging but essential for human-level experimental reasoning.

Verification and Provenance. Industrial and clinical applications require complete experimental provenance: every decision logged with reasoning traces, all parameters recorded, and outcomes traceable to specific model versions (Section 7.2).

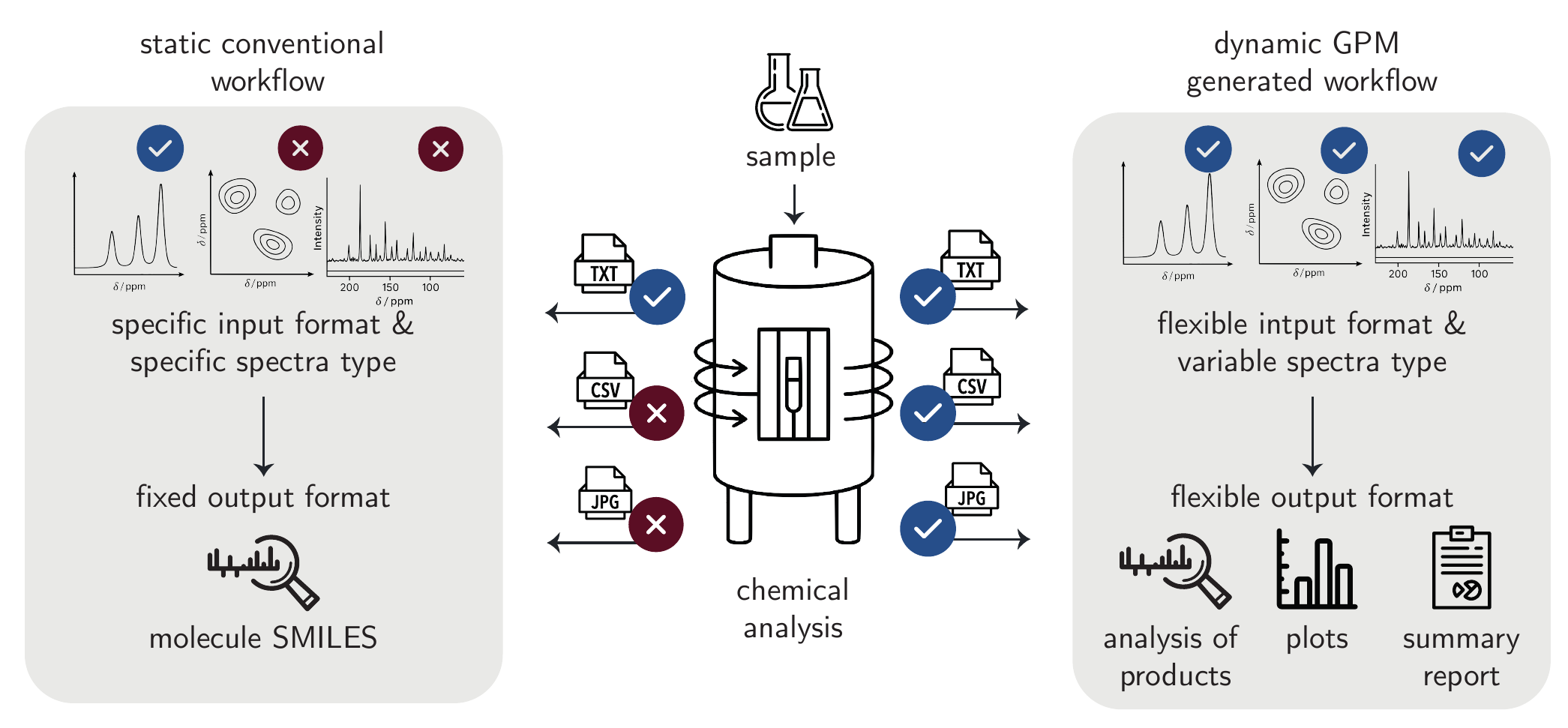

5.7 Data Analysis

The analysis of experimental data in chemistry remains a predominantly manual process.

One key challenge that makes automation particularly difficult is the extreme heterogeneity of chemical data sources. Laboratories often rely on a wide variety of instruments, some of which are decades old, rarely standardized, or unique in configuration.[Jablonka, Patiny, and Smit (2022)] These devices output data in incompatible, non-standardized, or poorly documented formats, each requiring specialized processing pipelines. Despite efforts like JCAMP-DX [McDonald and Wilks (1988)], standardization attempts remain limited and have generally failed to gain widespread use. This diversity makes rule-based or hard-coded solutions largely infeasible, as they cannot generalize across the long tail of edge cases and exceptions found in real-world workflows.

This complexity makes chemical data analysis a promising application for GPMs (Figure 5.7). These models handle diverse tasks and formats using implicit knowledge from broad training data. In other domains, LLMs have successfully processed heterogeneous tabular data and performed classical data analysis without task-specific training.[Narayan et al. (2022); Kayali et al. (2024)]

In chemistry, however, only a handful of studies have so far demonstrated similar capabilities. Early evaluations showed that GPMs can support basic workflows such as the classification of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) signals based on peak positions and intensities.[Fu et al. (2025); Curtò et al. (2024)]

Spectroscopic data often appear as raw plots or images, making direct interpretation by vision language model (VLM)s a more natural starting point for automated analysis. A broad assessment of VLM-based spectral analysis was introduced with the MaCBench benchmark [Alampara, Schilling-Wilhelmi, et al. (2025)], which systematically evaluates how VLMs interpret experimental data in chemistry and materials science—including various types of spectra such as infrared spectroscopy (IR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and X-ray diffraction (XRD)—directly from images. They showed that while VLMs can correctly extract isolated features from plots, the performance substantially drops in tasks requiring deeper spatial reasoning. To overcome these limitations, Kawchak (2024) explored two-step pipelines that decouple visual perception from chemical reasoning. First, the model interprets each spectrum individually (e.g., converting IR, NMR, or mass spectrometry (MS) images into textual peak descriptions), and second, a LLM analyzes these outputs to propose a molecular structure based on the molecular formula.

More complex agentic systems extend beyond single-step analysis and attempt to orchestrate entire workflows. For example, Ghareeb et al. (2025) developed a multi-agent system for assisting biological research with hypothesis generation (see Figure 5.3) and experimental analysis. Its data analysis agent Finch autonomously processes raw or preprocessed biological data, such as ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing or flow cytometry, by executing code in Jupyter notebooks and producing interpretable outputs. Currently, only these two data types are supported, and expert-designed prompts are still required to ensure reliable results.

Similarly, Mandal et al. (2024) introduced AILA, which utilizes LLM-agents to plan, execute, and iteratively refine full atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis pipelines. Compared to earlier prototypes, this systems emphasize transparency and reproducibility by producing both code and reports. The system handles tasks such as image processing, defect detection, clustering, and the extraction of physical parameters.

5.7.1 Limitations

While GPMs offer promising capabilities for automating scientific data analysis, several concrete limitations remain. Recent evaluations such as SciCode [Tian et al. (2024)] have shown that even state-of-the-art (SOTA) like GPT-4-Turbo frequently produce syntactically correct but semantically incorrect code, for instance, in common data analysis steps such as reading files, applying filters, or generating plots.

These technical shortcomings are further amplified by sensitivity to prompt formulation. As demonstrated by Yan and He (2020) and Alampara, Schilling-Wilhelmi, et al. (2025), even minor changes in wording or structure can lead to drastically different results, highlighting a lack of robustness in prompt-based control.

In practice, this means that robust prompting strategies, systematic validation, and human oversight remain essential components of any current deployment.

5.7.2 Open Challenges

Looking forward, several open challenges remain unresolved.

True Chemical Reasoning: It remains unclear whether current LLMs can perform genuine chemical analysis rather than relying on pattern-matching or shallow feature extraction. [Alampara, Schilling-Wilhelmi, et al. (2025); Alampara, Rı́os-Garcı́a, et al. (2025)]

Seamless Laboratory Integration: No commercial systems yet provide robust, end-to-end interoperability with the diverse analytical instruments used in chemistry laboratories. Existing research prototypes support only limited data types and still depend heavily on expert curation. [Ghareeb et al. (2025); Mandal et al. (2024)]

Standardization and Real-World Validation: Achieving production-ready systems requires progress not only in model robustness but also in data and protocol standardization, hardware integration, and thorough testing under realistic laboratory conditions. [Testini, Hernández-Orallo, and Pacchiardi (2025)]

5.8 Reporting

To share insights obtained from data analysis, one often converts them into scientific publications or other forms of content, such as reports or blogs. In this step, GPMs can also take a central role. While writing assistance has been showcased in past works, it remains limited in scope and real-world impact.

5.8.1 From Data to Explanation

The lack of explainability of ML predictions generates skepticism among experimental chemists[Wellawatte and Schwaller (2025)], hindering the wider adoption of such models.[Wellawatte, Seshadri, and White (2022)] One promising approach to address this challenge is to convey explanations of model predictions in natural language. An approach proposed by Wellawatte and Schwaller (2025) involves coupling LLMs with feature importance analysis tools, such as shapley additive explanations (SHAP) or local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME). In this framework, the LLM performs three key functions: First, it translates technical feature names into more accessible language. Second, using RAG over scientific literature, it retrieves relevant excerpts that explain the physicochemical relationships between identified molecular features and target properties. Third, it synthesizes these components into coherent natural language explanations that not only identify which structural features correlate with the property of interest, but also hypothesize why these relationships exist based on established chemical principles from the literature.

5.8.1.1 Writing Assistance

LLMs can assist with syntax improvement, redundancy identification,[Khalifa and Albadawy (2024)] figure and table captioning,[Hsu, Giles, and Huang (2021); Selivanov et al. (2023)] caption-figure matching,[Hsu et al. (2023)] and alt-text generation.[Singh, Wang, and Bragg (2024)] Models can be personalized for specific audiences or writing styles.[C. Li et al. (2023)]

LLMs has also been shown to potentially help complete submission checklists. Goldberg et al. (2024) found \(70\%\) of Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2025 authors found LLM assistance useful for checklist completion, with the same fraction revising their submissions based on model feedback.

5.8.2 Limitations

LLM explanations appear credible but often lack faithfulness to underlying reasoning.[Agarwal, Tanneru, and Lakkaraju (2024)] Models can reinforce existing biases through training data or prompting strategies.[Kobak et al. (2025)] While LLMs can process large datasets, they miss subtle artifacts and anomalies human researchers detect, and struggle distinguishing correlation from causation.[Jin et al. (2023)]

5.8.3 Open Challenges

Provenance Tracking Systems. Developing methods to trace every claim back to specific training examples or retrieved sources. This requires architectures that maintain explicit links between generated text and source materials, enabling verification of attribution completeness.

Authorship Frameworks. Defining contribution taxonomies that specify when LLM use constitutes co-authorship versus tool use. Journals and institutions need consensus guidelines for disclosure, attribution, and accountability when LLMs assist in research reporting.